English professor José B. Capino spent the summer of 2017 researching in European archives and interviewing people for his book on the late Lino Brocka, an influential Filipino filmmaker. He did not expect that his work would get two of Brocka’s most accomplished films—“Jaguar” and “Bona”—restored. Both films achieved one of the greatest honors that a film can receive: They were screened at the Cannes International Film Festival in 1979 and 1980, respectively. The latter returned to the festival this summer in Cannes Classics, a selection of the finest restored works of world cinema.

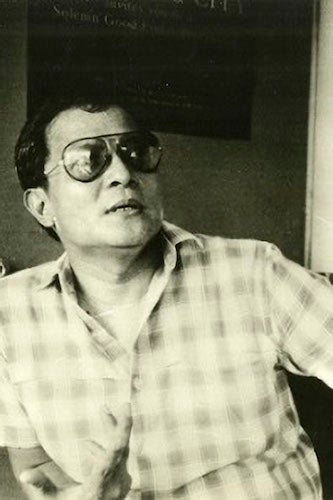

Lino Brocka (1939-1991) was a pioneer of cinema in the Philippines, where he created films opposing authoritarianism and depicting life under Ferdinand Marcos, who ruled as a dictator during the 1970s and 1980s before he was deposed in 1986. The Marcos dictatorship was marked by the deaths and mistreatment of many Filipino citizens, and Brocka’s films helped reveal these injustices to Philippine and international viewers.

His films also served as a basis for Capino’s 2020 book, “Martial Law Melodrama: Lino’s Brocka Cinema Politics,” which Capino researched in Europe with help from funds that he received as an LAS Conrad Humanities Scholar. A revised edition of the book was released late last year.

“This kind of funding supports the faculty and is crucial to their productivity as scholars,” Capino said. “I fully give credit to a very well spent Conrad fellowship for financing the vital last half of a 10-year book project.”

Capino’s research included an interview with French film director and film festival consultant Pierre Rissient, who had known Brocka quite well and was an advocate for non-European cinema at Cannes. It was during that interview in a Paris apartment in 2017 that Rissient revealed to Capino that negatives of “Bona” and “Jaguar” still existed. Rissient had been involved in preparing international versions of the two films and had advised Brocka to retain film elements in Europe.

Rissient, who passed away just a few months after the interview, entrusted Capino with the important information after hearing of his efforts to find and study prints of Brocka’s films all over Europe.

“Both of us got misty-eyed when that information was exchanged. It was a treasured moment in my career as a film scholar. Usually, I'm just reading stuff or watching films on my own at the archives,” Capino explained. “This was one of those moments when you work with people who have a genuine love for the movies and you make unique discoveries, or in this case, you get a tip that turns out to be extremely solid and does a lot of good for culture and humanity.”

Capino knew that he had to move quickly with the tip from Rissient. Too often, he said, film elements from historical filmmakers get auctioned off or held by collectors, or forgotten, and the lost films degrade over time. After some deliberation, Capino passed the information about the existence of the film elements of “Jaguar” to Stéphane Bouyer of Le chat qui fume, a small French film label that focuses on the restoration and distribution of films. Bouyer was able to locate the prints Capino had information about within a few days. Some time later, Capino offered the information about “Bona” to Kani Releasing, a two-person distribution outfit specializing in classic and new Asian films. Both firms began arrangements to restore the films.

That was the end of Capino’s involvement in the restoration projects, but the films’ journeys began anew. The screening rights to “Jaguar,” an action drama set in Manila’s slums, are still being cleared, but “Bona,” an 86-minute film originally released in 1980 that features a middle-class girl who drops out of high school after becoming obsessed with a handsome movie extra, was fully restored and shown at Cannes last May.

To know that he helped bring a nearly lost film back to life is very meaningful to Capino.

“To me, it's like a gift. It's one of those experiences that you have as a film scholar where you feel that you are working with people who dedicated their life to film art, to cinema,” Capino said. “You cross paths with them and even those fleeting encounters can produce lasting results. That film [“Bona”], because it was saved, will have an afterlife that will exceed my own in this world.”

Capino has not yet seen the restored version of “Bona.” He is waiting to see it projected on the big screen. Not only does a theatrical screening do justice to the film itself, but it’s a show of respect to the groundbreaking work done by film icons such as Pierre Rissient and Lino Brocka, Capino said.

“Having your film showcased in Cannes means that you are given a platform to sell your films so that they can be seen all over the world. So, Rissient entrusting me with that information, even though we had only met that one time, ultimately made it his last great present to Philippine cinema,” Capino explained. “I just fortunately happened to play the role of being a conduit for that gift. I was the person who passed it on, safeguarding a masterpiece of Philippine cinema for the future.”