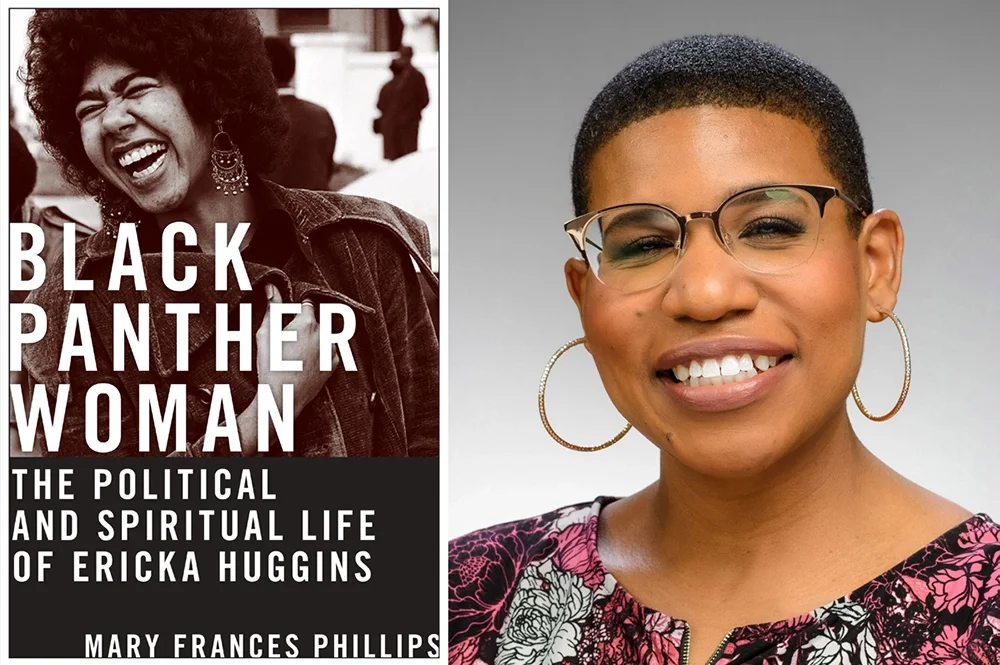

Political activist and educator Ericka Huggins used spiritual wellness practices to cope with imprisonment and racial oppression. Professor of African American studies Mary Frances Phillips wrote about Huggins and how her wellness practices and political work were deeply entwined. Her new book, “Black Panther Woman: The Political and Spiritual Life of Ericka Huggins,” is the first scholarly biography of a female member of the Black Panther Party.

When Phillips studied African American history in college, the material about the Black Panther Party was very male centered, leading her to wonder about the women who were missing from that history and what they contributed. The biography adds to the understanding of Black women’s political organizing and resistance, she said.

“Women were very much involved in the work of the Black Panther Party from the beginning, in every aspect of leadership. Many of the activities were heavily influenced by women. They were always there; they were just often left out of the public telling of the organization,” Phillips said. Women were often the ones keeping the organization and its community programs operating when the high-profile male leaders were targeted by the FBI, she said.

Phillips looked at Huggins’ childhood and her teenage and college years when she was active in student organizations and then joined the Black Panthers. But most of the book focuses on the two years, beginning in 1969, that Huggins spent in prison awaiting trial on charges in connection with the murder of a Black Panther member.

Those years were a turning point in Huggins’ life, when she began her wellness practices — yoga and meditation that she taught herself from a book provided by one of her legal team members who practiced yoga; writing poetry and prose; and working on women’s community-building initiatives. Huggins had a nearly 5-month-old daughter when she was imprisoned, and “she didn’t want her daughter to see her broken and sad and wilted. She wanted to be fully present for her daughter and she wanted to be well and healthy,” Phillips said.

Huggins was incarcerated with a small group of women who also were Black Panther Party members. They were considered political prisoners and were separated from the general population of the prison. The wellness practices that Huggins embraced were a form of resistance against the violence and racial oppression they encountered in prison, Phillips said.

Huggins co-founded a group in prison called the Sister Love Collective. One of its first acts was to start a hair salon. While doing one another’s hair, the women talked about their families and their troubles, and Huggins used her connections outside of prison to offer support by helping women get a lawyer or connect with family. The group established a bail fund for women. Phillips said the collective was doing grassroots political organizing in plain sight in the prison.

“To correctional officers, it looked very innocent. They thought they were just doing hair,” she said.

Huggins advocated for the humane treatment of prisoners by participating in food strikes to protest the lack of care for pregnant women and inadequate nutrition. She requested written documentation of the rules being enforced against them, refused medication and otherwise challenged authority, Phillips wrote in the book.

Huggins’ trial resulted in a hung jury, and the charges against her were dropped. After she was released from prison, she brought her wellness practices to her work with the Black Panther Party.

Huggins was best known for her educational work as director of the Black Panther Party’s Oakland Community School, an elementary school with a commitment to restorative justice. Students learned yoga and meditation to redirect their energy and recenter their focus on their schoolwork if they were misbehaving, Phillips said.

Huggins’ spiritual wellness work is influential today in movements such as Black Lives Matter, as well as in wellness groups, Phillips said.

“Spiritual practices and political practices go hand in hand. We do better political work when we’re engaged in spiritual practice as well. We’re able relate to each other spiritually, give more of ourselves and see things in a broader, fuller light,” she said. “It’s increasingly important in the moment we’re living in, when Black and brown people are under assault.”

Phillips established a sustained relationship with Huggins, interviewing her many times, along with her friends, colleagues and other Black Panther Party members. Her research examined the writings of Huggins and her peers, including letters she wrote while in prison, court and prison records, newspaper articles, and internal Black Panther Party memos.

Phillips said she used a narrative, storytelling style for the book, rather than an academic style, because she wanted it to have a broad reach and be accessible to the public. She said she sees the book as a toolkit to help teachers, students and activists use spiritual wellness to navigate the world.

“It’s a book that can serve the soul,” Phillips said.