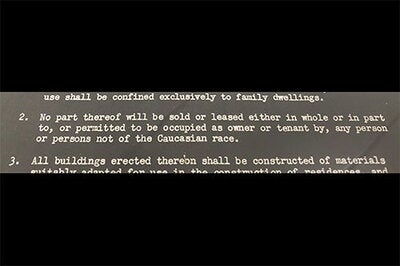

Aaron Ammons clearly remembers the first time he saw discriminatory property covenants in Champaign County. For certain neighborhoods, the detailed, legally binding documents that governed everything from building materials to curb cuts also included this: No non-Caucasians could live there.

What took his breath away, Ammons recalled, were the discriminatory covenants written by hand. Though they were written long ago, before the Civil Rights era, seeing them in perfect cursive drove home in chilling fashion the systemic nature of racism that they represented.

“It was like, ‘All houses have to be 20 feet from the curb, and no Black people can live there. Nothing special about it. Just how we do things here,” said the Champaign County clerk. “How can that sort of dehumanization be written into it with no alarm, with no one saying, ‘Hey, this is absolutely ridiculous’?”

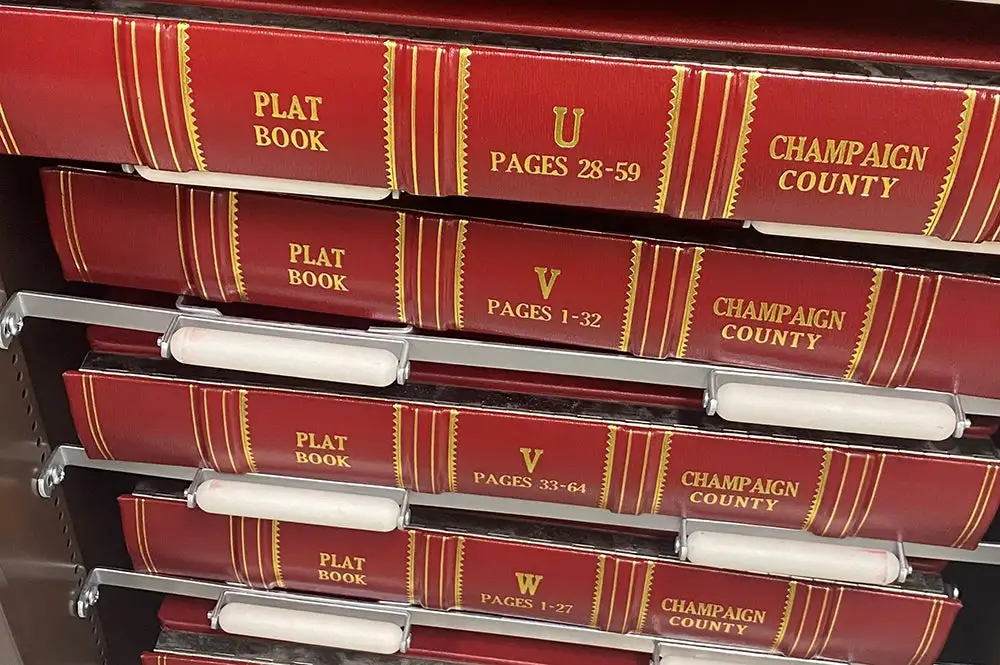

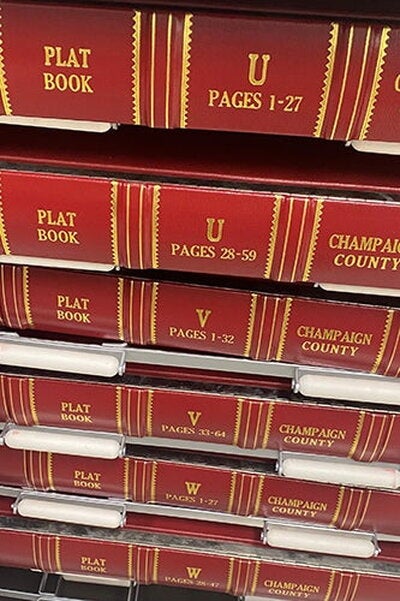

While those covenants are no longer valid in Illinois, they remain on the books in many locales and carry deep significance to many who are aware of them. In Champaign County, where 19 such covenants remain on the books, a task force founded by Ammons created the Restrictive Covenants Project to educate the public about the legacy of discrimination. Two LAS professors joined the cause.

Geography and geographic information science professor Marynia Kolak and psychology professor Eleanor Seaton have helped raise public awareness of the Restrictive Covenant Project while also planning to study and research discriminatory covenants and related topics. They joined the effort after hearing about it through the Center for Social & Behavioral Science at U of I, and the center continues to support them as they work with the project.

Kolak will study how these covenants and historical legacies of racism have affected the cotemporary landscape.

“If your ancestors weren’t allowed to live nearby the tree-lined streets and parks due to racism, weren’t allowed to start homes and gain and transfer wealth from generation to generation, that will impact what resources your family has today,” Kolak explained.

The discriminatory covenants can’t be destroyed or removed from the public record, but state law allows for them to be officially redacted if a property owner within that subdivision moves to do so. So far that process has resulted in two of the 19 discriminatory covenants being redacted in Champaign County.

Accounts and interviews of Black community elders could be an important part of this project, as they would be important to understanding the impact of these covenants on families, the professors said. An interactive map created through the Restrictive Covenants Project allows users to check if they live at an address that exists under discriminatory language.

“Place is different than space. While people may inhabit spaces, they make places,” Kolak said “As residents of Champaign-Urbana today, it’s important understand the place-making and resilience that was accomplished in the past by these elders and their communities, in spite of the racist policies that worked against them.”

Seaton’s research centers on the mental health of Black youth. She sees the Restrictive Covenants Project as an opportunity to consider racism on an institutional level and to speak with individual community members about their experiences.

“It’s important to me as a social scientist to use evidence like this to demonstrate the impact of racism, because in 2025 people still question whether racism exists,” Seaton said. “We document that these covenants go back to 1948 or 1951, etc., but we still see impacts today which also tells us about the long-term nature of racism and how it operates in this country, as well as the county and state level.”

The effects of this project are both professional and personal for the team. Both Ammons and Seaton reflected on their own family ties to the history of racism in the United States.

“I am a daughter of the Great Migration,” Seaton said. “My parents moved up to Chicago from Jim Crow Mississippi. I know all too well what can happen when people fight back against repressive regimes and racism at multiple levels, and this is the moment to do so. When it feels scary or threatening, it is the moment to do so.”

While the project is still within its early stages and working to raise grant money, the team is excited and hopeful about the change that it will bring.

“The bigger goal is to get people educated so they can join the fight to eradicate racism and that’s white, Black, Latina/o, Asian American, everyone,” Seaton said. “Whoever you may be, join the fight to eradicate racism in all of its forms throughout the entire country.”