In the 2003 science fiction flick The Core, a team of scientists drills to the center of the Earth in an attempt to restart the Earth's core, which has mysteriously stopped spinning, altering the planet's magnetic field and setting off catastrophic-if unrealistic-results. Disoriented birds crash into buildings, pacemakers fail to keep pace, and the orbiting Space Shuttle's navigation system goes haywire. Will the team be able to save the Earth in time?!

The reality of how the Earth's inner workings rotate is indeed much more fascinating than any cinematic version. No wonder the public's interest in the subject soared recently with the resolution of a nine-year debate regarding the speed of the core.

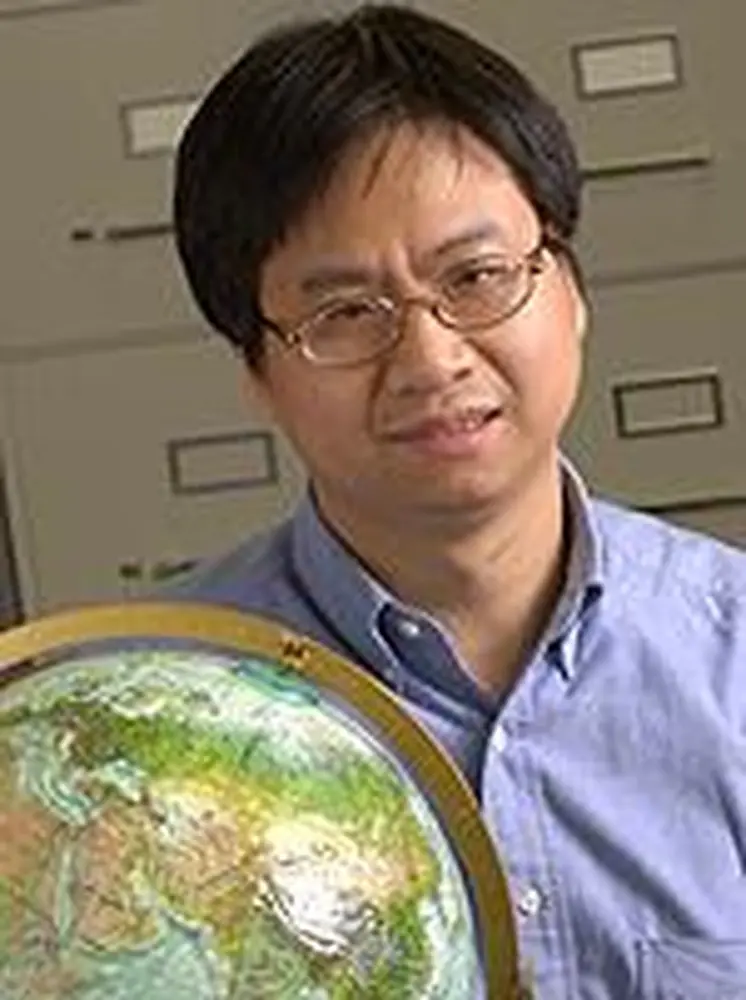

LAS geologist Xiaodong Song was the co-investigator of a study that found that the Earth's inner core rotates 0.3 to 0.5 degrees per year faster than the rest of the planet. Earth's iron core consists of a solid inner core 1,500 miles in diameter and a fluid outer core about 4,200 miles in diameter.

The inner core-about the size of the moon-plays an important role in the geodynamo that generates Earth's magnetic field, and an electromagnetic torque from the geodynamo is thought to drive the inner core to rotate relative to the mantle and crust.

Song and Paul Richards, a seismologist at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University, presented the first evidence for the faster rotation in 1996. Since then, some seismologists have suspected that flaws, or artifacts, in the data were responsible for the purported movement. Those questions have disappeared. "Extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof," says Song. "We believe we have that proof."

That proof came when Song and Richards measured 18 sets of seismic waves-"doublets"-from earthquakes in the South Sandwich Islands near Antarctica. The doublets, which were recorded at up to 58 seismic stations in and near Alaska with a time separation of up to 35 years, allowed the researchers to detect temporal changes along the sampling paths. For example, in a 2003 seismic event, when waves moved through the inner core they arrived one-tenth of a second faster than those from a similar occurrence in 1993.

"The similar seismic waves that passed through the inner core show systematic changes in travel times and wave shapes when the two events of the doublet are separated in time by several years," Song says. "The only plausible explanation is a motion of the inner core. The magnetic field generated in the outer core diffuses into the inner core, where it generates an electric current. The interaction of that electric current with the magnetic field causes the inner core to spin, like the armature in an electric motor."

The fluid outer core decouples the solid inner core's movement from the mantle. Because the fluid outer core is not very viscous, frictional drag is small. "Differential rotation is a fundamental dynamic process that goes to the heart of the origin of our planet and how it has evolved," Song says. "There is still much to learn about the inner Earth."

University of Washington seismologist Kenneth Creager, writing in Science, states that Song's research "removes any lingering doubt as to whether the inner core is rotating at a different rate than the mantle."

Response to Song's discovery has been widespread. The New York Times, National Geographic, Washington Post, CNN, ABC, the BBC, and The Bangladesh Times are just a few of the media outlets that have written stories.

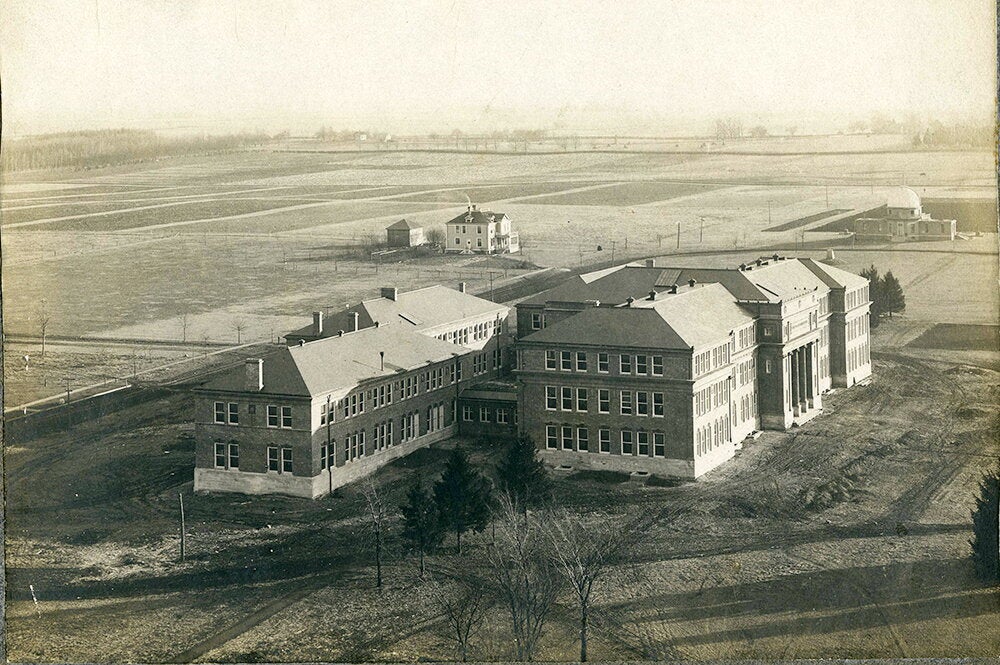

The interest hardly surprises Steve Marshak, head of LAS's Department of Geology. "The story resonated with the public because it describes such a fundamental feature of the Earth, and sets the stage perhaps for the eventual determination of how the Earth's magnetic field works."

Song and Richards were assisted by U. of I. graduate students Yingchun Li and Xinlei Sun, Columbia graduate student Jian Zhang, and research scientist Felix Waldhauser. The U.S. National Science Foundation and the Natural Science Foundation of China funded the work.