There are walks in the park and then there are walks that affect the course of university history for the next 128 years, and the campus tour that a botany professor named Thomas Burrill gave to Eugene Davenport in 1895 was one of those. Nobody knew it at the time, however.

Davenport was a talented, 30-something professor from Michigan being wooed to lead agricultural studies at the University of Illinois. The problem? Agricultural studies at Illinois, at that time, were virtually non-existent: The program was confined to a couple of classrooms and an assortment of neglected livestock pens and farm fields south of Green Street. Only nine students at Illinois were enrolled in agricultural studies.

If there was one person who could convince Davenport to take the job it was Burrill, the magnetic longtime professor who by then was regent of the university. He was most renowned for his groundbreaking studies of plant pathology in the College of Science, a predecessor of the College of LAS.

“As we stood by the dilapidated fences and pens (Burrill) remarked, ‘It’s pretty bad, isn’t it, Professor Davenport?’” wrote Davenport later, in a memoir. “I assented with emphasis. ‘But,’ said (Burrill), sweeping the horizon with his arm and that wonderful eye of his, ‘this is Illinois, and Illinois is an imperial state able to do anything that she considers worthwhile for her welfare.’ No promise. No bombast. But it was that gesture and that vision together with the possibilities of such a state that decided me to cast my lot with Illinois, a decision I have never regretted even in the darkest days that were to come.’”

Davenport joined Illinois as dean of the College of Agriculture, and over the next few years he relied heavily upon the friendship, advice, and what he called the “prophetic vision” of Burrill as he reversed the fortunes of agricultural studies. This included winning the trust of Illinois farmers, who, still angry that the university had dropped its original name of Illinois Industrial University, were skeptical of the university’s commitment to agriculture. Davenport eventually turned these skeptics into stout supporters who advocated for the university at the state legislature.

Davenport also faced skeptics at the university, particularly President Andrew Draper, who believed that agriculture could be taught as a vocation. Davenport, however, was a firm believer that future farmers needed not only technical knowledge but a solid, four-year degree that included science and even literature.

“(The university) exists not for the service of men only but for women as well; not for personal service merely but for the development of the industries and of the state,” Davenport wrote in an essay, “The spirit of the land-grant institutions.”

“(The university) no longer confines itself to teaching approved courses in stock knowledge to the young,” he wrote, “but is active, even aggressive, in the discovery and application of new truth wherever it can be useful in the development of the state, material as well as human, economic as well as social.”

In 1899 the state legislature approved not only $150,000 for the construction of a new agriculture building but also directed additional annual funding from the Morrill Acts to agricultural studies. When Davenport Hall was completed in 1901 (it was initially called the Agriculture Building, only to be renamed in 1947), it was called the largest university building devoted to the study of agriculture in the United States.

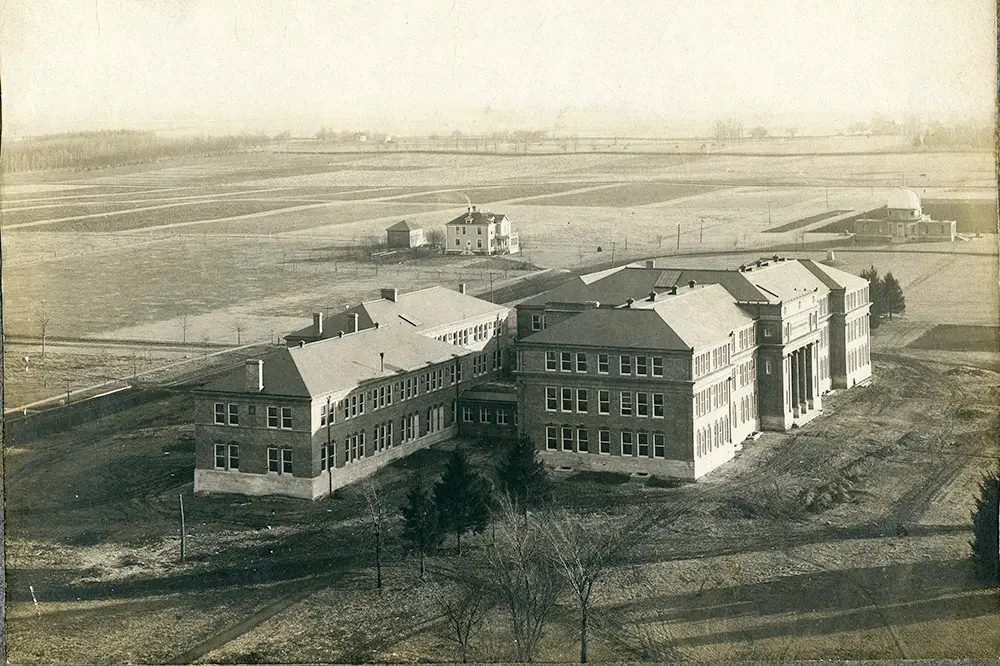

The construction of Davenport Hall also ushered in a new era for the campus layout. Aside from the Observatory (which opened in 1896), Davenport Hall stood virtually alone on what was then south campus. The building, however, fulfilled the eastern outline of what planners had been envisioning, in one form or another, for a few years: an expanse of lawns and open space for students to unwind and relax. In 1902, the New Chemical Laboratory (later Noyes Laboratory) went up immediately to Davenport’s north, and in 1905 campus built the Women’s Building (later renamed the English Building) some 200 feet to the west. The Auditorium (later Foellinger) was built in 1907 to the southwest of Davenport, thus—with Natural History Building, Harker Hall, University Hall (later replaced by Illini Union), and Altgeld Hall forming the north edge—completing the outline of the Main Quad.

Upon completion, Davenport Hall occupied 2 acres of floor space and consisted of a main building, 250 feet long, and two wings, each 116 feet long.

It held space for dairy manufacturers and household science, farm machinery, and veterinary science and stock judging, with the main building holding classrooms, laboratories, the state entomologist, and the agricultural experiment station, and a 500-seat assembly room.

Ironically, the building soon proved too small for agricultural studies, particularly as farm machinery grew in size and scope. By the early 1920s, campus began adding new agriculture buildings on south campus and planned to turn over Davenport Hall to the College of LAS. That transition took place over the span of decades, but today the building is entirely occupied by LAS, with classrooms, offices, and laboratories devoted to geology, geography and geographic information science, anthropology, and chemical and biomolecular engineering. More than 6,300 students per week pass through Davenport Hall.

Over the years buildings sprung up all around Davenport Hall, so much so that, back in 1895, Burrill and Davenport wouldn’t have recognized what the once forlorn landscape would turn into. In fact, now, if you enter Davenport Hall, you can embark upon a maze of walkways, connected space, and underground tunnels that connect a succession of some of the most important scientific buildings on campus: Chemistry Annex, Noyes Laboratory, Roger Adams Laboratory, Chemical & Life Sciences Laboratory, and Morrill Hall. At the very end of the walk you’d enter another landmark building that anchors the opposite end of the interesting journey: Burrill Hall.