Ninety years from now, the Chicago fire could be a good description of the heat on the street, not just a reference to the blaze that destroyed the city in 1871.

By the year 2100, depending on carbon dioxide emissions, the average annual temperature in Chicago could rise by anywhere from 3 to 8 degrees Farenheit, according to findings in the recently released report Climate Change and Chicago, published by the city and commissioned by Mayor Richard Daley in 2006. In addition, the number of summer days over 90 degrees in Chicago could reach as many as 80 in one year and the number of days over 100 degrees could be close to 30.

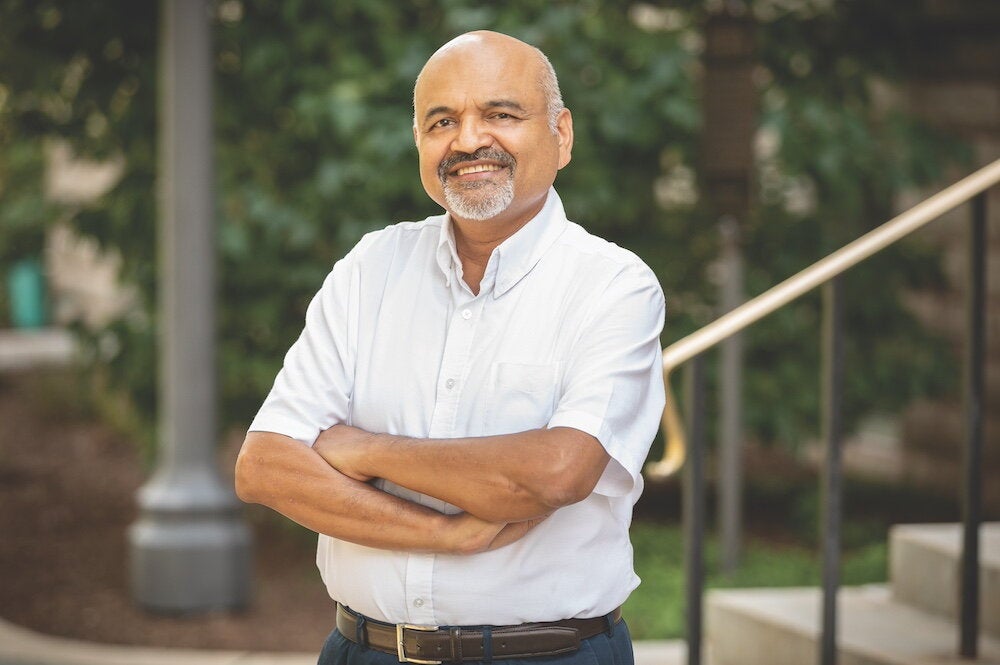

Don Wuebbles, an LAS professor in atmospheric sciences, was lead author of the city’s climate report, along with his former graduate student Katharine Hayhoe of Texas Tech University. Wuebbles led the scientific analysis, using a little over 100 years of weather data collected at 15 stations in the Chicago area. The result was Chicago’s first long-range climate forecast.

According to Wuebbles, the climate science team considered two scenarios for Chicago in making their projections. In the low scenario, they assumed that the global economy would eventually make a dramatic move away from fossil fuels to alternative energy sources by 2100. In the high scenario, researchers assumed that only about 25 percent of the globe’s energy production would switch away from fossil fuels by 2100. Fossil fuels are responsible for high levels of carbon in the atmosphere, which have been implicated in changing the global climate.

Under the low scenario, they project that carbon dioxide concentrations would rise to 550 parts per million by the year 2100; and under the high scenario, concentrations would reach 950 parts per million. Current carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere are around 385 parts per million.

These projections translate into a 3- to 4-degree increase in average annual temperatures with the low scenario and a 7- to 8-degree boost with the high scenario by the end of the century. The number of possible 90-plus-degree days in a year could be 38 with the low scenario and 80 with the high scenario; and the number of 100-plus-degree days could be eight with the low scenario and 31 with the high scenario.

Today, Chicago averages about 15 days over 90 degrees and two days over 100 degrees.

Under such conditions, Wuebbles says the Chicago climate during the summer would feel more like that of Atlanta, Ga., under the low scenario and Mobile, Ala., under the high scenario.

“When some people hear this, they say that’s not a bad thing,” Wuebbles points out. “They say they won’t have to go to Texas or Florida in the winter. But then I say wait a minute. I have to make it clear that this is what the summer climate would be like—not the winter climate.”

Wuebbles says the winter climate in Chicago would be more on par with Harrisburg, Pa.—warmer but with roughly the same amount of snow as now. The report projects more overall precipitation, both rain and snowfall, in the winter and spring than there is today—but less or equal precipitation in the fall and summer. In addition, the precipitation will be more likely to come in large storm events.

“So it ends up with a strange situation,” he says. “There will be a higher probability of floods and a higher probability of droughts at the same time.”

In addition to examining the effects of global warming on temperatures and precipitation, Chicago’s report analyzes what this means for human health and welfare, air quality, disease outbreaks, hydrology, local ecosystems, and Chicago’s infrastructure and economy.

For instance, there would be more heat waves such as the one that baked Chicago in 1995, which led to almost 700 deaths. Events such as the 1995 heat wave could occur several times each summer under the high scenario by the end of the century, raising serious health concerns. Therefore, the city is putting into place adaptation measures to avoid such health repercussions.

According to Wuebbles, Chicago is one of the first large cities to make this kind of an assessment and the first to determine specific steps it will take to reduce its emissions of carbon dioxide, which accounts for nearly half of the total emissions of the state of Illinois. The city has set the ambitious goal of an 80 percent reduction in 1990 levels of carbon dioxide emissions by the year 2050.

“Otherwise, climate change could alter the very character of the Chicago area,” Wuebbles says.

For more details on the report, go to the Chicago Climate Action Plan website at www.chicagoclimateaction.org.