Papaya farmers can be a funny sort. Ask them if they’d rather have a boy or girl, and without hesitation every last one of them will say “hermaphrodite”—if they’re talking about papayas, of course. A plant biologist at U of I is working to grant them their wish.

Papayas are male, female, or hermaphrodite, but only hermaphrodites produce the flavorful fruit that’s sold commercially. This is an expensive problem for farmers because until they mature and flower nobody can figure out what gender they are.

This means that papaya farmers must plant five or more seeds together to maximize the likelihood of obtaining at least one hermaphroditic plant. Once they identify a desired plant they cut the others down. The problem is that the process is labor intensive, expensive, and leads to crowding that stymies root systems and delays fruit production.

With help from a $3.1 million grant from the National Science Foundation, however, U of I plant biologist Ray Ming is leading an effort to develop papayas that produce only hermaphroditic offspring, which would improve papaya health while cutting farmers’ costs and their use of fertilizers and water.

“We’re going to change the sex of the papaya to help the farmers,” says Ming, who will lead the effort with researchers from the Hawaii Agriculture Research Center, Texas A&M University, and Miami University. A USDA scientist will also collaborate on the initiative.

“This is a perfect case to demonstrate how basic science can help the farmers directly,” Ming says. “In our case we can apply it immediately as a byproduct of the research program.”

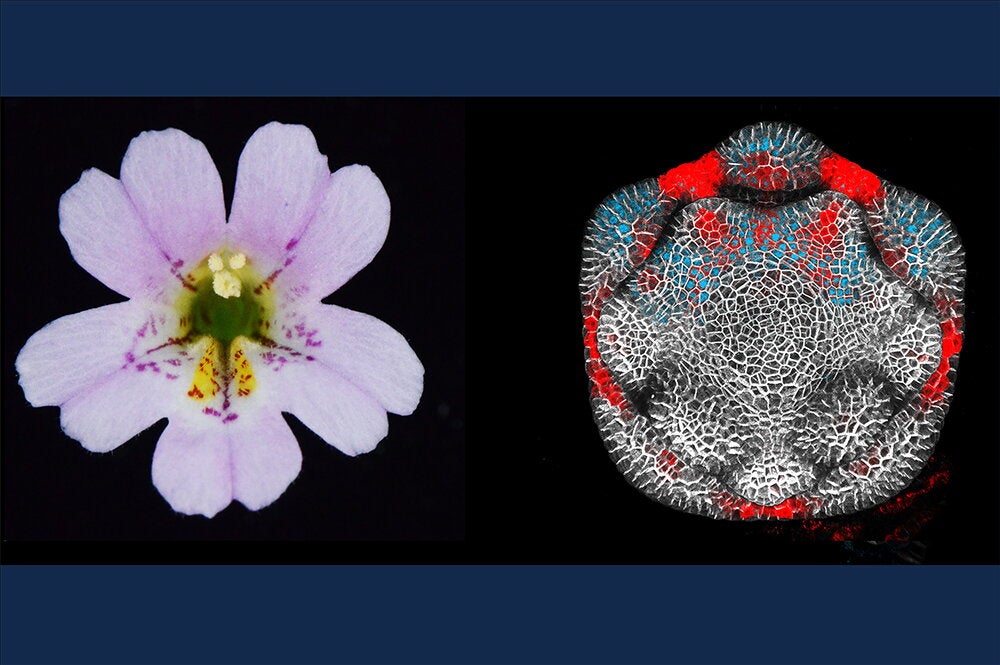

Ming co-led an international team that produced a first draft of the papaya genome in 2008. This draft, which sequenced more than 90 percent of the plant’s genes, offered new insights into the evolution of flowering plants in general, and the unusual sexual evolution of the papaya.

With genetic research, Ming says, they will be able to alter the papaya female genome by adding the genome responsible for the male reproductive organ. That will transform the female genome into a hermaphrodite, and the resulting plant will produce only hermaphrodite seeds and eliminate a major headache for farmers while helping papayas and the environment.

Further research will explore the origin and evolution of the sex chromosomes by comparing the papaya to five other related species in two genera, and by conducting population genetic studies of the papaya sex chromosomes.