If you ever find a periodic table published between 1926 and World War II, you might notice the two-letter abbreviation for Illinois—Il—listed as element 61. No, it’s not a printing mistake, and yes, it carries a reference to the University of Illinois. It stands for illinium, the name of which has since been removed from the periodic table and yet remains a symbol of how science evolves.

The story of illinium ended with a lot of disappointment at Illinois, but nearly 90 years later it’s remembered as one of the Department of Chemistry’s first appearances as a renowned research program. Because of illinium, many people around the world for the first time recognized the quality of science that was occurring here even as the scientific process itself eventually took illinium off the charts.

“Sometimes discoveries are thought to be made and then evidence shows that it really isn’t that way,” Greg Girolami, professor of chemistry, says in a documentary for UI-7 describing the search for the so-called Illinois element. “This is one of those stories.”

Granted, researchers at Illinois weren’t the only ones who ultimately failed to find the elusive element 61, which for years existed only in theory. In a 2009 article titled, “Illinium: An Impeached Element,” Lee Marek (BS ’68, chemical engineering), notes in the Journal of Chemical Education that element 61—today called promethium—was one of the most confounding of all the rare earths, and that it was “discovered” seven times before its existence was proven conclusively in 1944 at Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

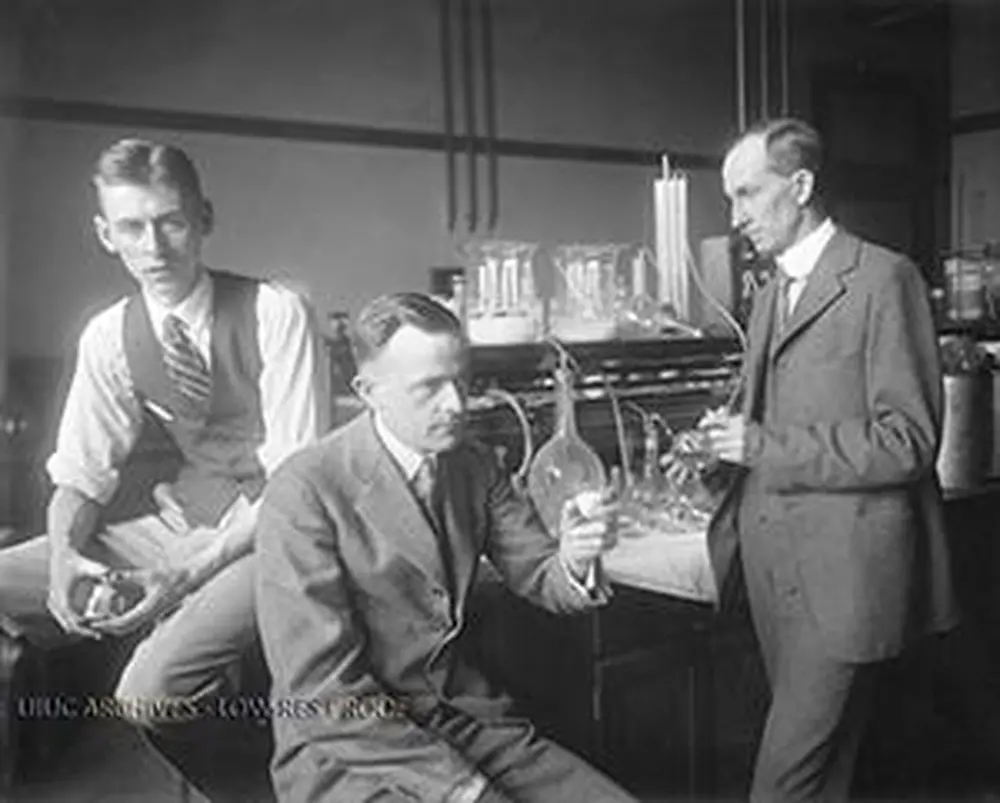

The work by B. Smith Hopkins and his colleagues at Illinois, however, was compelling enough that much of the world believed them when they announced in 1926 that they had painstakingly crushed, separated, and analyzed some 400 lbs. of ore and collected half a gram of element 61.

The news was greeted with great excitement on campus and in the science world. There was a parade, music, and a banquet attended by Nobel Prize-winning scientists. Time magazine mentioned Hopkins in the same breath as the Nobel Prize, and much of the chemistry world went along with Hopkins’ suggestion that the element be named illinium.

Skeptics remained, however, and as the years passed, Hopkins and his colleagues were unable to confirm the results of their original study. Today, chemists know that Hopkins (and many others around the world) were working on a faulty assumption. As Marek notes, Oak Ridge researchers found the element by analyzing byproducts of uranium fission, and revealed that element 61 does not occur naturally on Earth. (Since then, it’s been observed in the spectrum of the star HR465 in the Andromeda constellation.)

That’s why, by the end of the 1940s, they knew that Hopkins and his colleagues had not discovered element 61, and the name illinium disappeared from the periodic tables. The reputation of Illinois, however, remained intact.

“It shows us that at one time the University of Illinois was making its first entrance onto the international stage in terms of a powerhouse in scientific research,” Girolami says. “And so it shows us a little glimpse into that period of our university’s history.”