Growing up in Chicago’s Hyde Park-Kenwood neighborhood, Audrey Petty would pass the imposing Chicago Housing Authority’s Robert Taylor Homes on the way to piano lessons. Those 28 drab, concrete high-rises, containing more than 4,400 apartments arranged in horseshoe clusters along the Dan Ryan Expressway, were practically visible from Petty’s doorstep, and yet she saw them as a foreign, mysterious, and impenetrable enclave.

“I felt like they were places that were apart—that I would never get in there,” says Petty, now an English professor at Illinois. “I was aware, through headline news, of tragic events and difficult conditions at Robert Taylor and other large high-rise developments—crime, drug sales, an underground economy—but they were places that I was really curious about.”

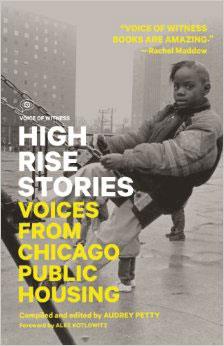

The Robert Taylor Homes are gone now, demolished as part of Chicago’s “Plan for Transformation” to improve neighborhoods. In a way, however, Petty has finally entered those high-rises, and in a way few ever have, which she documents in her recently published—and now nationally acclaimed—book, High-Rise Stories: Voices from Chicago Public Housing.

Prompted by Petty’s desire to know about the people displaced by the transformation project, the book contains personal narratives of a dozen former residents who Petty and a team of Illinois graduate students (Michael Burns, Eric Tanavutti, and Crystal Thomas) found by posting fliers in schools, libraries, and social service agencies. From a former gang member who could clean and reassemble a gun by age five, to the president of the Cabrini Green resident council (described by President George. H.W. Bush as a “model for the nation”), they tell their stories about life in the high-rises in intimate, conversational tones. Petty and her team conducted as many as 10 interviews with each subject.

“Each of these people could have their own book,” Petty says. “I’m just able to present the tip of the iceberg.”

The result is compelling enough that the stories have won praise, reviews, and coverage from the Chicago Tribune to the Wall Street Journal, Harper’s Magazine, and other print, online, and radio slots across the country.

“The timeline regarding public housing history and other materials in the book’s six appendices will become essential historical resources,” writes Bill Savage, in the Chicago Tribune. “But the book’s primary value comes from the narratives of former [Chicago Housing Authority] tenants. The range of speakers exemplifies the diversity of people who formerly lived in the projects, from ex-cons trying to straighten out their lives to youthful idealists.”

The stories they shared with Petty include a complete inventory of horrors: elevators that didn’t work; stairwells with no lights; infestations of vermin, drug dealers, and gangsters; abusive police; indifferent paramedics; the violent deaths of neighbors, friends, and family members.

But these same memories are commingled with recollections of roller skating, basketball, a drum and bugle corps and, for a while at least, an on-site library at Robert Taylor Homes. Neighbors often functioned as extended family members, babysitting for each other’s children and sharing holiday cooking. One narrator, “Dawn,” recalls creating stereo systems from discarded electronics found in the Cabrini-Green incinerator. She is now a professional disc jockey.

“One of the things that holds the whole book together is that people share stories of some sort of crisis—a human rights crisis they experienced while they lived in high-rise public housing,” Petty says.