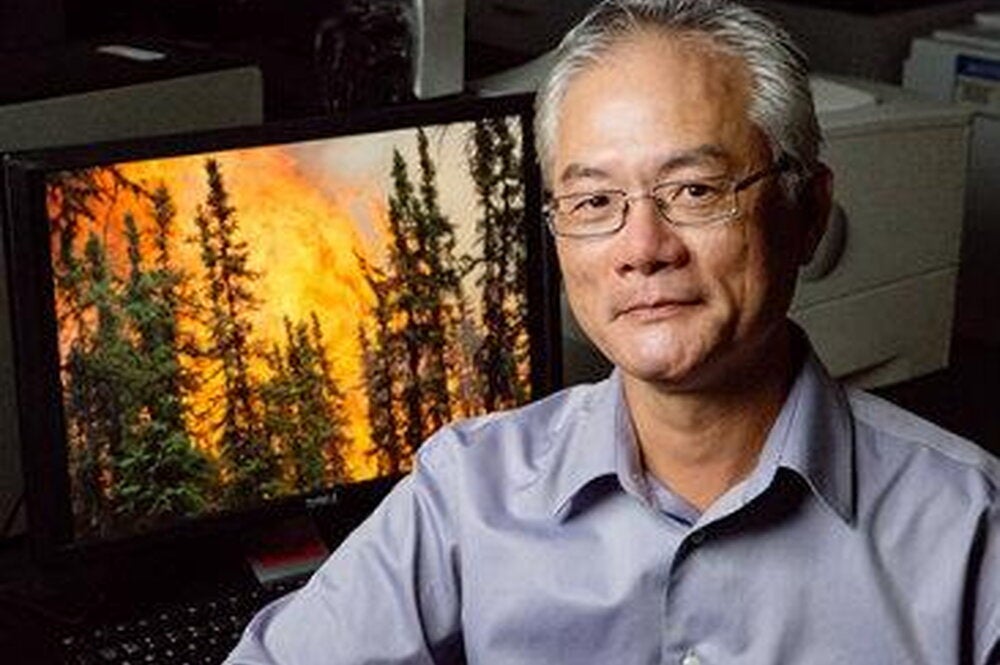

While the recent Groundhog Day snowstorm was a headache to millions of people from Chicago to Maine, it was nothing but enlightenment at 40,000 feet, where University of Illinois professor of atmospheric sciences Bob Rauber was on the maiden scientific voyage of a new radar system that provided a view of snow like nobody has seen before.

As the massive Nor’easter pounded Boston and other areas in New England, Rauber, head of the Department of Atmospheric Sciences, and colleagues from the National Center for Atmospheric Research flew above it in a specially equipped Gulfstream V airplane carrying a new cloud radar that’s been in development for several years.

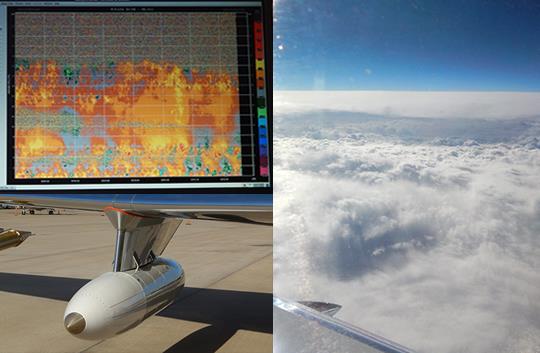

In brief, Rauber says, the flight provided a virtual blizzard of data as the wing-mounted Doppler radar helped scientists see patterns in the weather system that they never knew existed.

“To give you an idea of how I’d describe it, I’d liken the standard radar that we use in atmospheric research to wearing glasses made out of the bottoms of Coke bottles,” Rauber says. “This new radar is like putting on a pair of fine-tuned 20/20 glasses. You can see circulations that simply can’t be seen with a normal radar.”

The plane they used, owned by the National Science Foundation, is called HIAPER, short for High-performance Instrumented Airborne Platform for Environmental Research. Accordingly the new radar, developed by the National Center for Atmospheric Research, is called HIAPER Cloud Radar, and Rauber believes it can drastically improve our understanding of storms and weather.

Rauber, the first scientist to utilize HIAPER Cloud Radar outside of test runs, plans to use the data he collected on February 2 to better understand how heavy snow bands form in storm systems.

“Where the heavy snow falls and how it’s organized depends on how the fine scale structure of the storm becomes organized,” he says. “The new radar can see the vertical circulations in the clouds very clearly, and we can also see all sorts of other structures that exist, whether the air is rising quickly, which will produce more snow and what are called generating cells, and different types of wave motions, and so on.”

The flight on February 2 was also noteworthy for the rapid turnaround between the time they recognized that the storm was forming and actually flying out to study it, Rauber notes. In the past, field studies in atmospheric science have required years of planning, but last fall Rauber pitched the idea to NSF of having their plane and the new radar system available on short notice to study storm systems as they form.

Developing a scheme to make the plane available on short notice, Rauber adds, could also help scientists study other events that don’t leave much time to plan for, such as hurricanes and ash plumes thrown out by volcanoes.

NSF liked the idea, agreeing to make the aircraft available on short notice in February. It so happened that three Nor’easters—ideal for Rauber’s study of snow bands given how ocean air interacts with the storm—struck the east coast in late January and early February. As the third one advanced on the east coast from the west, Rauber flew to Raleigh, N.C., to meet the NSF plane and its crew, which consisted of pilots, engineers, and a project manager from the National Center for Atmospheric Research. Rauber was the chief scientist.

They took off at about 7 a.m. on February 2, soared above the storm between Washington, D.C., and Maine for eight hours, and returned to Raleigh by 3:30 p.m. with enough data to fuel at least a couple years of research, Rauber says.

“We all have a lot of work to do, a lot of quality controlling the data. This is the first time that data’s been collected in a storm with this radar,” Rauber says. “We have to be especially careful about the analysis. But I can tell you that everybody on the plane was looking at the data coming in, and saying, ‘What on Earth?’ We were just seeing so many exciting structures in these clouds that we just didn’t anticipate would be there.”