A $45 million reinvestment in U of I's Realizing Increased Photosynthetic Efficiency (RIPE) research project, which has already garnered international attention for demonstrating dramatic yield increases in food crops, will help researchers advance their work to address the global food challenge.

The five-year reinvestment from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Foundation for Food and Agriculture Research, and the U.K. Department for International Development, builds upon the Gates Foundation's initial, $25 million grant in 2012 that eventually helped RIPE researchers demonstrate a 20 percent increase in crop yields by making plant photosynthesis more efficient. Researchers hope the reinvestment, announced today, will eventually lead to increases of up to 50 percent within decades.

“Today's report on world hunger and nutrition from five UN agencies reinforces our mission to work doggedly to provide new means to eradicate world hunger and malnutrition by 2030 and beyond,” said RIPE Director Stephen Long, the Gutgsell Endowed Professor of Crop Sciences and Plant Biology at the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology at Illinois.

“This investment is timely," he said. "Annual yield gains are stagnating and means to achieve substantial improvement must be developed now if we are to provide sufficient food for a growing and increasingly urban world population when food production must also adapt sustainably to a changing climate.”

According to RIPE Deputy Director Don Ort, USDA/ARS Photosynthesis Research Unit and the Robert Emerson Professor in Plant Biology and Crop Sciences at Illinois, more than one research strategy will be required to continue improving how plants use light to grow and produce.

“While no single strategy is going to get us there, our successes in redesigning photosynthesis are exciting,” Ort said. “RIPE has validated that photosynthesis can be engineered to be more efficient to help close the gap between the trajectory of yield increase and the trajectory of demand increase.”

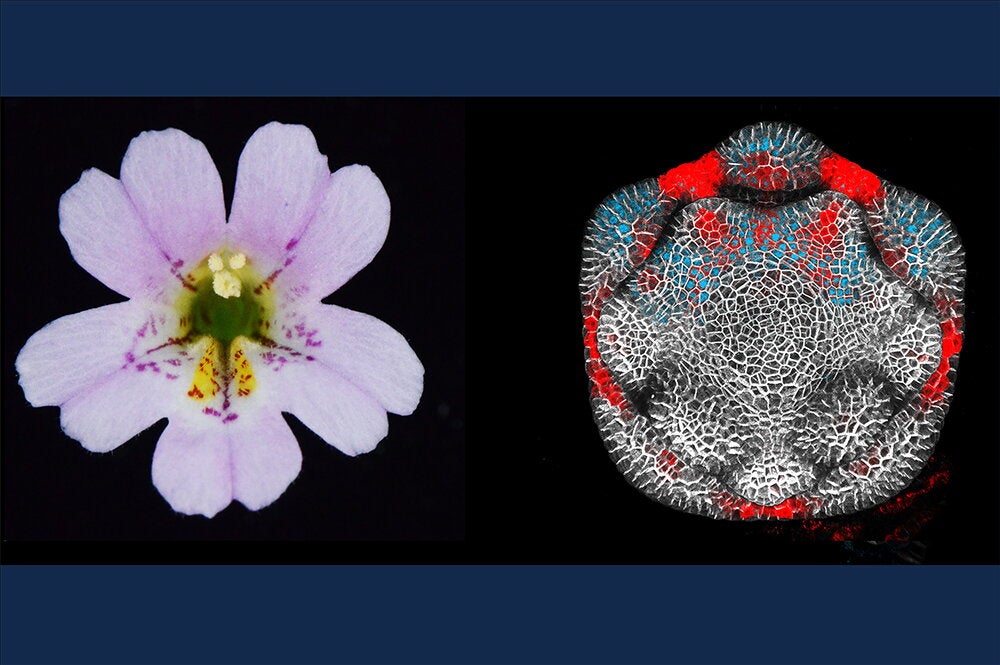

RIPE researchers simulated the 170-step process of photosynthesis, building on half a century of photosynthesis research at Illinois. They used their computer models to identify seven potential pipelines to improve photosynthesis, and with the support of an initial $25 million, five-year grant from the Gates Foundation, began work in 2012 to turn their ideas into sustainable yield increases.

Last year, in a study published in the journal Science, the team demonstrated that one of these approaches could increase crop productivity by as much as 20 percent, which was a dramatic increase over typical annual yield gains of 1 percent or less. Two other RIPE pipelines have now led to even greater yield improvements in greenhouse and preliminary field trials.

“Our modeling predicts that several of these improvements can be combined to achieve additive yield increases, providing real hope that a 50 percent yield increase in just three decades is possible,” Long said. “With the reinvestment, a central priority will be to move these improved photosynthesis traits into commodity crops of the developed world, like soybeans, as well as crops that matter in the developing world, including cassava and cowpeas.”

RIPE and its funders will ensure that their high-yielding food crops are globally available and affordable for smallholder farmers to help feed the world’s hungriest and reduce poverty, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia.

But much work and research remain before such high yields become a widespread reality, Long said.

“It takes about fifteen years from discovery until crops with these transformative biotechnologies are available for farmers,” he said. “It will therefore be well into the 2030s before such superior crops are seen at scale in farmers’ fields.”