It’s widely known that cats, dogs and other furry friends see the world differently than we do. But what about animals that are a little bit below the surface — like fish?

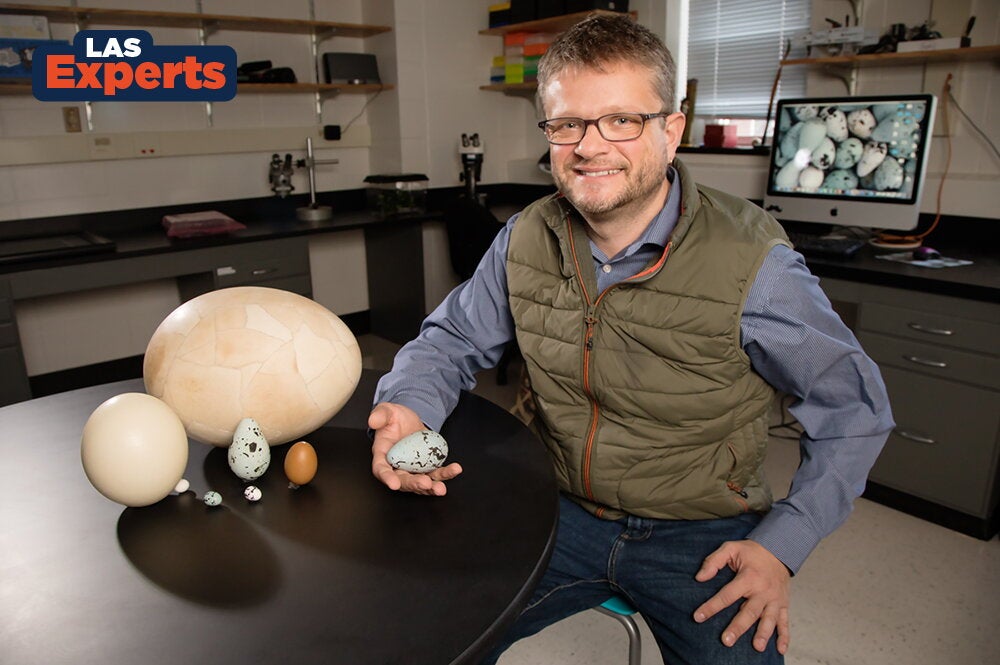

Until now, there hasn’t actually been much research into the topic, but thanks to Becky Fuller, professor of animal biology in the School of Integrative Biology, there’s now an iPhone app that helps people see the world as a fish would, at least when it comes to largemouth bass.

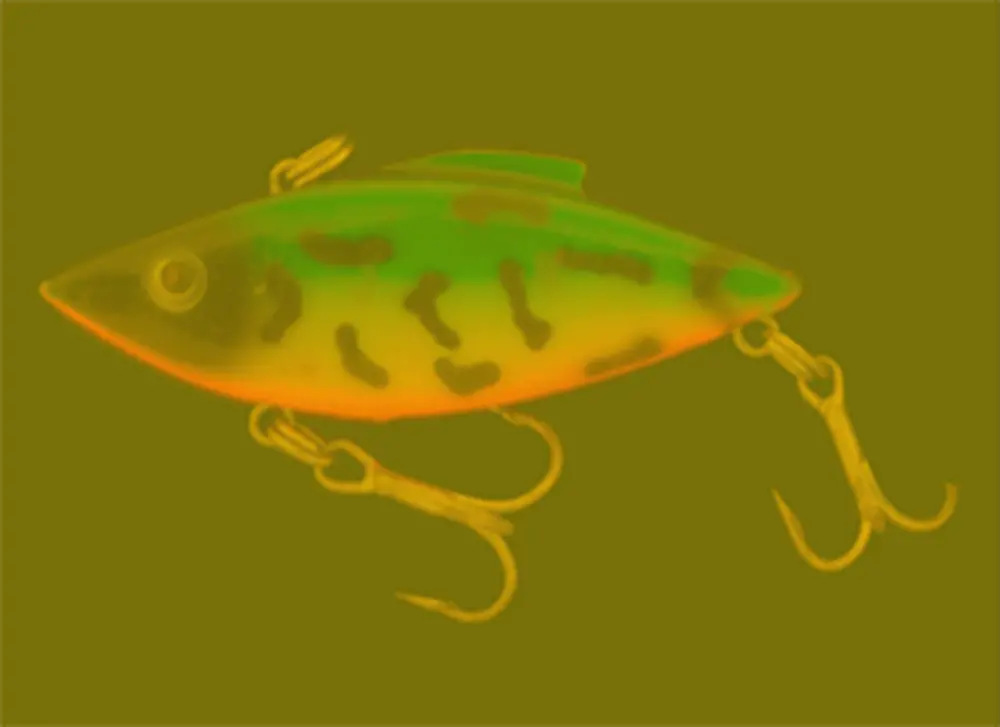

Fuller’s app, BassVision, which she created with help from Information Technology Services at Illinois, as well as her colleagues at BassInSight, a small company where she is president, is intended to help anglers catch bass by showing how the fish see their lures.

“We’ve known for a long time that the visual properties that humans have are different than that of animals, and it can differ in a whole bunch of ways,” Fuller said. “It can differ in the number of cone cells that are in the retina — which is one of the huge ways bass and humans differ.”

While humans have three cone cells—a blue, a green, and a red—bass only have two cone cells, which lends them an entirely different perspective.

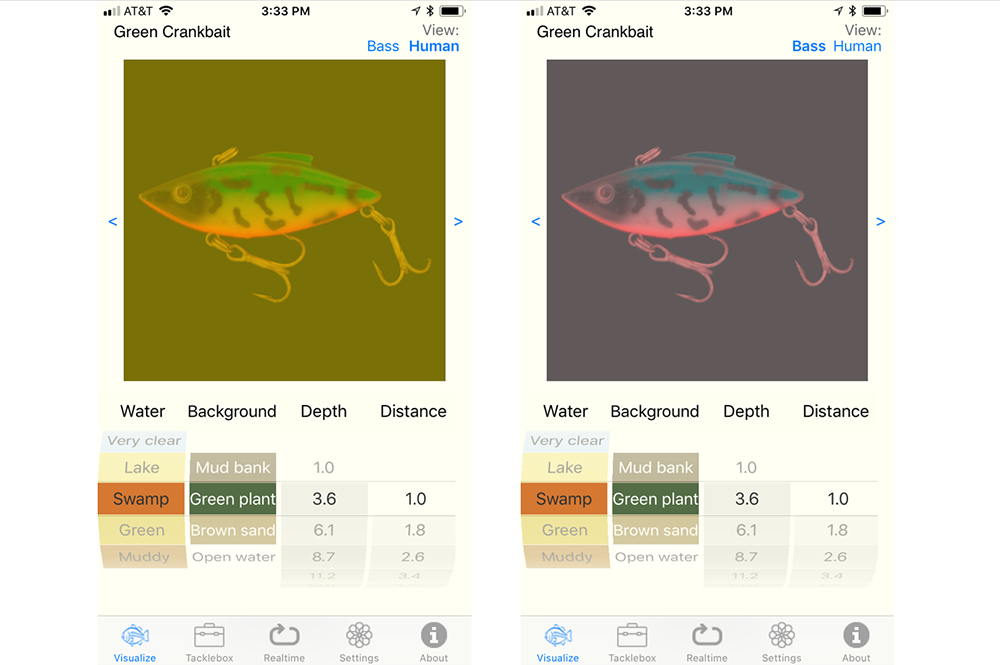

Using BassVision, the user is able to see what a lure might look like to a bass given different conditions, such as various water depths and lighting, so that lures can be adjusted or chosen to increase the likelihood that a bass sees them.

Fuller refers to the app as a “digital tackle box of the future,” noting that it’s useful for anglers of any skill level in the multibillion dollar bass industry. High school kids just getting into fishing, for example, might want to find out what lure is best, while even professionals might want a little extra help, she said.

“Those guys have their strategy set out, but there are times and certain conditions when they say, ‘Yesterday I got everything to bite and now nothing’s biting.’ They might look at the app and get some help with that as well,” Fuller said.

The app allows the user to compare how things appear for humans versus how they appear for bass. The user can choose from a large selection of lures already featured on the app and alter water type, background type, depth, and distance to see exactly how the bait will appear to the bass.

There’s also a real-time visualizer component, which means anglers can hold up a lure in front of their phone camera and see how the bass will see the bait.

“The app also takes into consideration the time of day, the cloud cover, and where you are on Earth,” Fuller said.

In the future, Fuller said the app will have extended properties and could even be used as a database for water-types in the local region, and could potentially display water properties in real time.

While apps exist for users to stimulate dog and cat vision, this app simulating fish eyesight is the first of its kind. Fuller stumbled upon the idea of researching bass eyesight as she studied the Bluefin killifish, a fish that bass like to eat.

“Some of the Bluefin killifish are red, some of them are blue, some of them are yellow, it differs in different habitat types,” Fuller said. “So I started to wonder how the bass see those patterns and how does it differ in a clear spring versus a swamp.”

Determining how bass see color wasn’t easy. Fuller and the graduate student who helped her painted different turkey basters different colors and then trained the bass to prefer certain colors. Some of the bass were trained to prefer red, some were trained to perform green, and some were trained to prefer yellow.

The finding? Bass can see some colors as humans would. They are good at seeing red and green. But other colors such as yellow and blue appear differently to them. Bass see yellow as white and blue as black. These results match the predictions of the simulations in the BassVision app.

BassVision launched Labor Day weekend and thus far is a success, given that they’ve hardly publicized the app yet.

“The things that fish have to do because they’re in the aquatic environment really is night and day different than what terrestrial organisms have to do,” Fuller said. “Trying to understand their world is sort of a fun little puzzle to crack.”