McCollum v. Board of Education, the landmark 1948 U.S. Supreme Court case which upheld the separation of church and state in public schools, didn’t originate with a fiery sermon or philosophical debate. It began at a small, wooden desk in a school hallway in Champaign, Illinois.

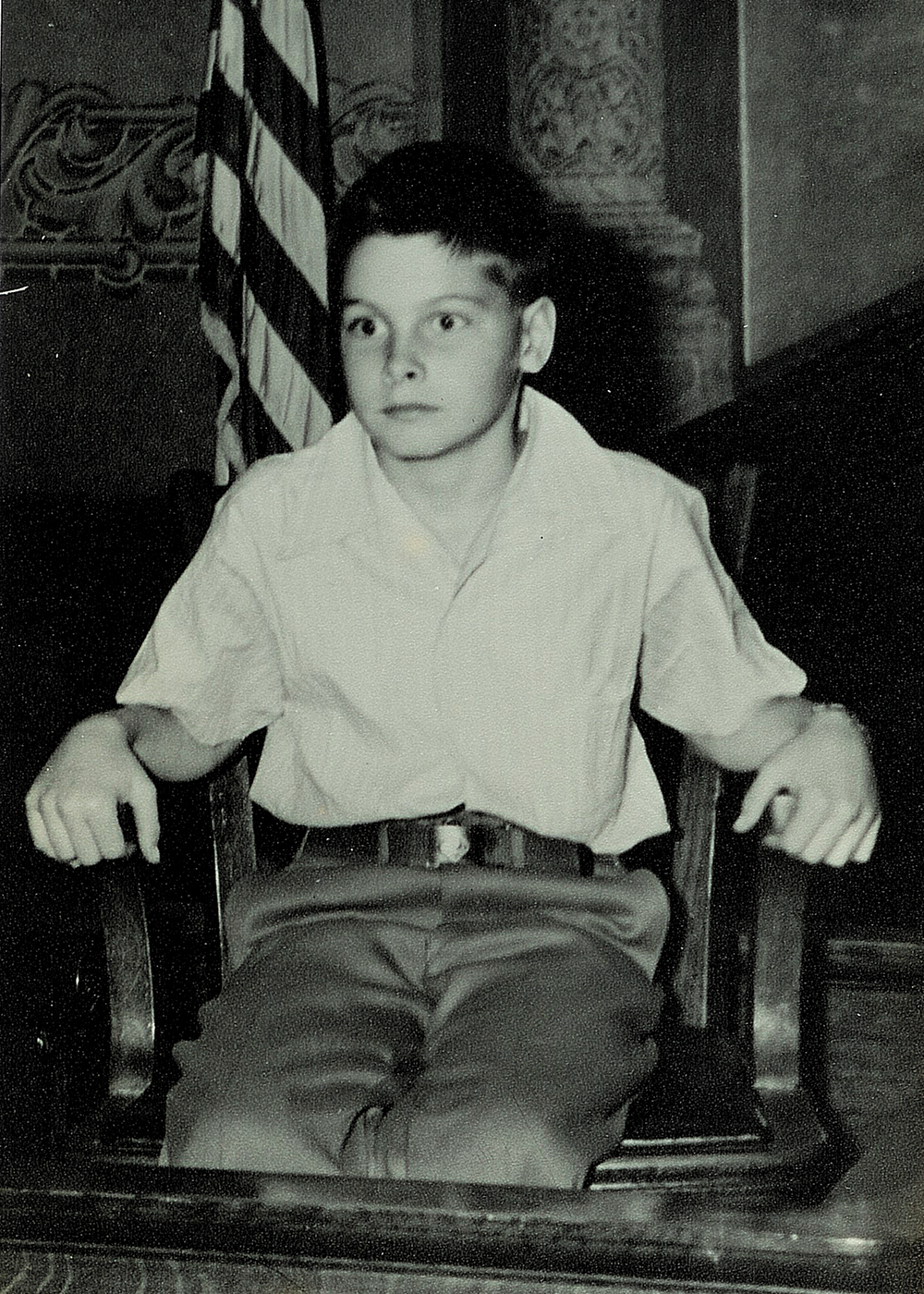

That’s where public school officials would put James (Jim) McCollum when he chose not to attend voluntary fifth-grade religious education classes. It was the seat for kids who misbehaved— and that didn’t sit well with his mother, Vashti McCollum (AB, ’44 general curriculum; MA, ’57, social science).

She went to the school superintendent to complain. When told there was nothing that the schools could do, the issue grew in significance for Vashti, and she filed suit in the 6th Judicial Circuit court in Champaign County to bar religious education classes from public schools. The court ruled against McCollum, so she brought the case to the Illinois Supreme Court. In 1946, the Illinois Supreme Court upheld the circuit court ruling.

Vashti, a mother of three, didn’t give up the fight, however, and in June 1947 the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear the case.

“Every once in a while, history messes with the wrong person,” said Vashti’s middle son, Dannel (BA, ’58, science and letters; BS, ’68, secondary education; MS, ’94, geography), in a 2010 interview about his mother. Dannel once served as mayor of Champaign, and his book, “The Lord is Not on Trial Here,” became the basis for a PBS documentary.

Small in stature but possessed with what her children describe as a strong personality, Vashti would need every bit of her strength to endure what happened as her case gained national attention. Champaign in the mid1940s, said Jim (BS, ’56, geology; JD, ’62, law) in an interview with LAS News, was extremely pious, and reaction against the McCollums was strong as people perceived Vashti’s case as being anti-religious.

Trick-or-treaters pelted the family with rotten food, the New York Times reported, and someone strangled the family’s cat. Vashti was threatened and lost her job as a dance instructor at U of I. Daily life for Jim grew so tense that his parents (Jim’s father, John, was a professor in the Department of Horticulture at Illinois) sent him to live with his grandparents in New York.

The family’s support for Vashti never wavered, however. In fact, Jim, her oldest son, said that he looked to his mother for his own strength. “I was calm, because she was calm,” Jim said. “I was rarely scared. Even when my family received threats and I started to get into fights at school, I was calm.”

Jim was careful to point out that although Vashti self-identified as an atheist, the home she built was not antireligious. Religion, Jim recalled, simply was not a topic of discussion in their home, even though Vashti’s name ironically appears in the Bible as queen of Ahasuerus, the Persian King. According to the Book of Esther, the queen refused to obey her husband’s order and was divorced.

“I think (my mother) found pride in her name and her beliefs,” Jim said.

Vashti’s religious views were also influenced by her father, Arthur Cromwell, who was also an atheist and the president of the Rochester, New York, Society of Free Thinkers. In the 2010 interview, Dannel recalled Cromwell refusing to swear on the Bible prior to giving court testimony during the case.

That’s at least partly why, when Jim was in fourth grade—a year prior to his mother’s clashes with school officials that eventually led to the U.S. Supreme Court case—and he actually wanted to attend religious education courses, Vashti balked at the idea. But Jim was curious, and he was also feeling pressure to join the classes.

“The pressure—to some extent from my peers but particularly from the fourth-grade teacher—made me want to be included in whatever was going on in there!” Jim said.

Vashti and John eventually relented and allowed Jim to attend the religious education classes. But after taking a few classes, Jim found the material uninteresting, so by the fifth grade he was opting out of the class. That’s what landed him in the desk in the hall, and how he became singled out by his classmates and teachers.

“When I was punished for not being a member of the class, my mother got involved,” Jim said.

Once the case reached the courts, Vashti contended that the religious education classes were a misuse of taxpayers’ money, discriminated against non-Christian faiths, and were an unconstitutional merger of church and state. She was not without friends and sympathizers—a local Unitarian minister and a group of Jewish businessmen in Chicago supported her, according to news reports.

However, her arguments didn’t find much traction in the courts until they reached the U.S. Supreme Court. There, on March 8, 1948, after testimony from both Vashti and Jim, the court ruled 8-1 in Vashti’s favor.

Justice Hugo L. Black, who wrote the majority opinion, said the practice of religious education in Champaign schools was “beyond all question” using tax-established and tax-supported schools “to aid religious groups to spread their faith.” He added, “It falls squarely under the ban of the First Amendment.”

The ruling in the case is considered a precursor to decades of legal debate over school prayer, religious displays on public property, and other matters regarding the separation of church and state. As for Vashti, she earned her master’s degree after the case was over, and spent much of the rest of her life traveling. She wrote a book on the case, “One Woman’s Fight,” and served two terms as the president of the American Humanist Association. Vashti passed away in 2006 at age 93.

Jim, meanwhile, now lives in Arkansas and was a chapter founder for the Americans United for Separation of Church and State. He recalled his mother fondly—and what she stood for.

“As long as the public school is used to recruit the child,” she once said, “or to segregate the children according to religion or to use the truancy power of the public schools to make them go to religious training or religious instruction classes, I’m against it.”