One morning last summer, a half dozen Illinois students climbed into cars and drove east of campus. They passed a few miles of houses and farmland before they turned onto a country road and parked near something unusual, at least for these parts. It was a forest.

They put on their boots. They had a lot of work to do—and that’s an understatement, on the scale of giving someone a straw and saying, “We have a lot of work to do before we empty this pool.” The students’ job was to document every single tree in that forest, from saplings angling for sunlight to stately giants with trunks more than a meter in diameter.

There’s a unique kind of magnetism emanating from Trelease Woods. Partly because of its close proximity to the University of Illinois, which owns it, and partly because it’s so old and rare, the 60-some acres of woodland is one of the most-researched tracts of forest in the world.

Nobody really knows how old it is, other than it pre-dates the United States as we know it. Trelease Woods is one of the last remaining fragments of the Big Grove, a prairie forest that existed for centuries in east-central Illinois before white settlers arrived in the early 1800s. Most of the Big Grove subsequently fell to loggers, but somehow Trelease Woods eluded the axe until 1917, when it was acquired by the university. Today it’s managed by the University of Illinois Committee on Natural Areas, and it has much to offer researchers and students.

Named for William Trelease, an eminent early 20th century botany professor at Illinois, Trelease Woods is host to several classes each year, from integrative biology to civil and environmental engineering. It’s the site of numerous, important research projects on topics ranging from butterfly ecology to mosquito control and genetics.

Carol Augspurger, for example, professor emeritus of plant biology, has been visiting Trelease Woods every week for 27 years to study the effects of climate change on forest phenology: the timing of leaf budding, expansion, coloration, and dropping. She collaborates with Chunyuan Diao, professor of geography and geographic information science (GGIS), to compare satellite and drone data with observations on dozens of plant species that Augspurger has made in Trelease Woods.

Gene Robinson, professor of entomology and director of the Carl W. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology, conducts molecular analysis on bees in Trelease Woods. The researchers are interested in identifying genes that orchestrate changes in social behavior and genes whose activity are affected by changes in the social environment.

“Trelease Woods,” Robinson said, “has been integral to our lab’s success.”

There’s also much to be learned from Trelease Woods about forest ecology. That’s why the students were there that morning last summer—and many mornings after that. They were collecting data for a research project led by Jim Dalling, head of the Department of Plant Biology, and Jennifer Fraterrigo, professor of natural resources and environmental sciences in the College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences.

If you had joined them, however, you might get the feeling that this research touched on something deeper than plotting coordinates and measuring tree diameters. Maybe you’d sense it before you even reached the tree line and peered into the dark, green gloom, and heard the creak of trunks, the scream of a hawk, or the knocking of a red-headed woodpecker on a hickory. Maybe you’d sense it when you spotted the shadows of behemoths: massive bur and chinkapin oaks, some of which were saplings about the time that Galileo was arrested for arguing that Earth revolved around the sun.

A tree census

Dalling has been teaching ecology classes in Trelease Woods since 2006, but this particular tree census is part of his first research project there. Dalling’s background is in tropical forest research; prior to coming to Illinois, he participated in a census of 250,000 trees in Panama.

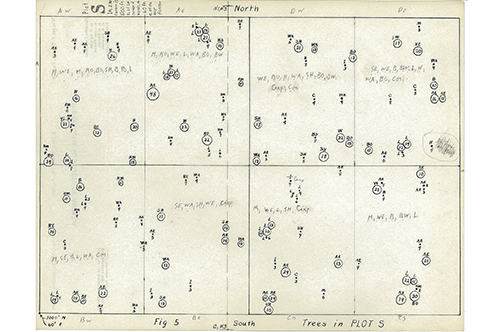

Recently, however, he came across departmental records about a tree census conducted in Trelease Woods in 1936 by eminent ecologist Arthur Vestal. It had thorough notes and locations for every tree in the forest. For someone interested in forest ecology, the old notes were invaluable.

“From Vestal’s work and an earlier paper in 1920, we know how many trees there were of each individual species and where they were distributed in the forest,” Dalling said. “There was probably nowhere else in North America where we can look back through time and see how the forest has changed.”

More tree censuses were conducted periodically in Trelease Woods from 1936 to 1948, and in 1964, 1976, 1986, and 2004. Some of the trees, Dalling said, appear to be 400 to 500 years old. Intrigued, Dalling, in collaboration with Fraterrigo, began a new tree census at Trelease Woods, with support from a grant from the U of I's Student Sustainability Committee. The census, which will map and measure more than 40,000 trees, should be complete by this fall. The ecological “big data” generated by this project will be used by future students who visit Trelease Woods to study forest ecology.

They’re adding their research findings to ForestGEO, a worldwide network of researchers devoted to long-term studies of forests. The network includes more than 6 million trees in 70 research forests in 27 countries, but no sites have been documented for as long as Trelease Woods.

The researchers already know some things. For example, 80 years ago elm and ash trees filled Trelease Woods, but as they fell to disease and beetle infestation, sugar maples have taken their place. In 1922, there were 31 tree species in Trelease Woods; now there are about 20. And, Dalling notes, Trelease Woods has somehow been remarkably resilient to invasive species. There are very few non-native species in the woods.

Trelease Woods can also provide key insights into how carbon storage in deciduous forests has changed. As the number of fast-growing (and fast-decaying) sugar maples has increased, and the number of hard-wooded elms, ash, and oaks has decreased, Dalling said, the amount of carbon stored in the woods is on the decline.

There is, he said, a lot more to be learned.

Measuring the woods

The students filled buckets with their gear: iPads, tape measures, calipers, laser range finders, tags, hammers, nails, water resistant blue paint, and bug repellent. They split into teams, and although only 100 or 150 meters separated their work zones, the undergrowth in Trelease Woods was thick enough that most of the time they couldn’t see or hear each other.

Guided by a grid system established by researchers in the 1930s, the teams worked their way methodically through the thickets, documenting every tree with a trunk wider than 1 cm at chest height. A team could cover about 600 square meters of forest each day—a decent-sized patch of woods, but just a fraction of the roughly 250,000 square meters that make up Trelease Woods.

They identified trees—as time went on, their printed tree guides became less and less necessary—and measured trunks with tape measures or calipers. They plotted locations using range finders, documented each tree in an iPad, tagged them, and marked them with a touch of blue paint.

As they worked, they learned other lessons from Trelease Woods: Teamwork, the nitty gritty (and sometimes creepy, crawly) realities of field research, and how to be precise and accurate in the face of the organic chaos that is an ancient forest.

April Wendling, who recently earned dual bachelor’s degrees in Earth, society, and environmental sustainability and GGIS, said that she’s learning tree species identification skills, how to do field work, and other knowledge applicable to other labs and jobs.

“I grew up sheltered in the Chicago suburbs, so this is a new experience,” she said. “I’m enjoying it. I’m getting torn up by mosquitos, but I’m enjoying it.”

It turns out that counting trees is a good way to learn appreciation for the woods. For Alan Sherrill, a senior majoring in natural resources and environmental science and minoring in GGIS, working in the woods is an unexpected life development. He grew up playing videogames and working in fast food restaurants, but now he speaks about the forest with an environmental consciousness that might have made John Muir smile.

“Something like a tree falling can happen, and then there’s a succession. It opens up the light and allows undergrowth to grow. Soon there’s a meadow of flowers because of the opening,” Sherrill said. “It’s crazy how things can change so rapidly from a tree falling in the woods.”

Nearby, Caterina Kim, a sophomore in integrative biology honors, and Laura Goralka, a senior in integrative biology, plotted their way through the trees. Kim wants to someday pursue a career in animal ecology and conservation; Goralka wants to pursue nursing.

“It’s not my career path,” Goralka said, of the tree census, “but it’s definitely about the experience of working in a lab and working with people. I’m thinking about being a research nurse.”

Kim said this is one of her first jobs. “I think I’m learning how to take very precise and accurate data, and also working with a team, which is something I think is great,” she said.

The pair made good progress as the morning wore on, but small things began to occur that reminded them of the still significant gap between their world and this one. They stumbled across a deer carcass; a wicked-looking spider temporarily delayed a trunk measurement. As they sought their bearings, Kim pointed toward an old research marker pounded into the forest floor.

“Do you see that yellow post?” Kim said. Goralka squinted into the underbrush, but the light was diffuse, and the angles and colors presented by the woods were strange. Try as she might, Goralka couldn’t see it, even though it was just a few yards away.

To watch a video about the Trelease Woods tree census, visit go.las.illinois.edu/TreleaseWoodsVideo.

Editor's note: This story first appeared in the Fall 2019 issue of LAS News magazine. It has been altered from the print version to reflect the correct spelling of Caterina Kim.