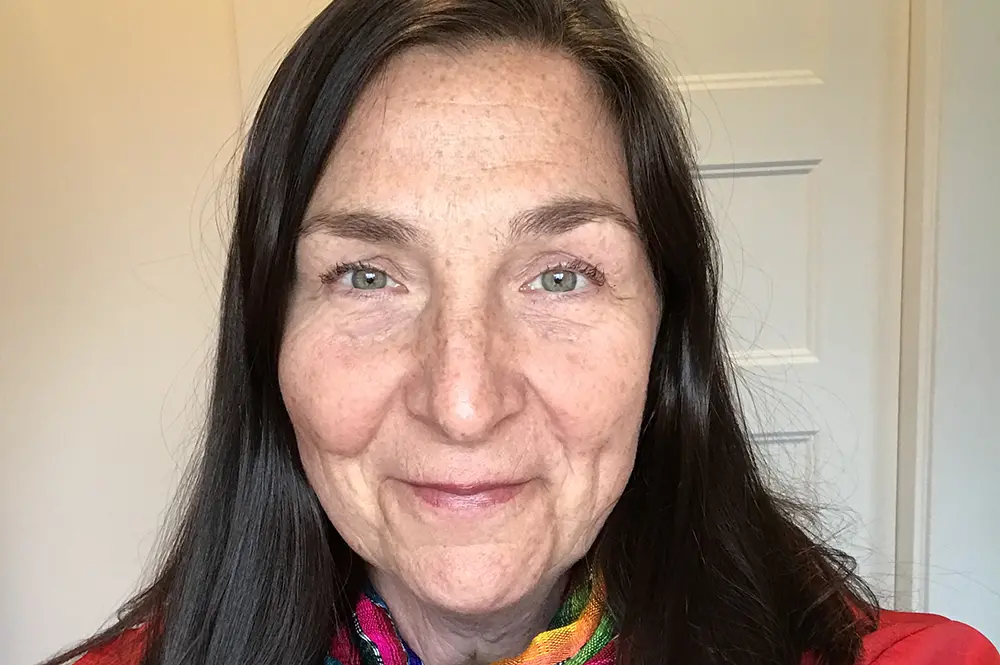

Pediatrician Alison Kirby (BS ’84, biology) was part of a 35-doctor practice in Walla Walla, Washington, when the principal of an alternative school first asked her to do free physicals for the kids joining their basketball team.

Lincoln High School in Walla Walla is for students whose behavior or academic problems bumped them out of the main high school. Lincoln’s new principal thought that a basketball program might help to keep students in school, but players needed physicals to qualify.

“I said sure, send them over,” Kirby recalls. “But as I began to see these students, I asked them when was the last time they’d been to see a doctor. They’d say, ‘Not since kindergarten.’ How could that be? These were 16- to 17-year-old boys!

“So, I went to a school meeting about truancy, and it was like a gentle slap of reality,” she continues. “I found we had kids missing school because of dental abscesses and untreated strep throat. I thought: ‘What? What?’”

Kirby decided to take action, and she co-founded a school-based health clinic that helped to turn around both the school and the lives of hundreds of students. The clinic and school have drawn nationwide attention, even being featured in “Paper Tigers,” a documentary about Lincoln High School directed by Robert Redford’s son, Jamie.

For her tireless efforts, Kirby has received the 2019 LAS Alumni Humanitarian Award.

Kirby grew up in Dwight, a farm town 45 minutes west of Kankakee. Her mother became an early role model when she took a stand and convinced the community that it needed an ambulance and paramedic program. Serious accidents were common as large semis roared through town, but the nearest hospital was 45 minutes to an hour away.

“It made a difference seeing my mom’s tenacity, doing the right thing at her own cost,” she said.

Coming from a working-class background, Kirby was the first person in her family to attend college when she came to the University of Illinois, obtaining her bachelor’s in biology in 1984. After receiving her MD at Southern Illinois University, she did her residency in Portland, Oregon. She also began doing volunteer work at the Greenhouse Clinic for street kids.

“I saw things at the clinic that I had only read about,” she recalled. “It was like third-world medicine. I saw kids with middle ear infections that normally you would just treat with antibiotics. But the infection had broken through the ear, and they had infections in the bone around the ear, and the whole side of their face was swollen.”

Kirby volunteered at the Greenhouse Clinic from 1988 until 2000, when she and her family moved to Walla Walla. There, she began raising eyebrows among other physicians in her practice whenever she would see low-income patients for free.

“But in those days, I was sassy, and I still did it,” she said.

Once she started doing the free physicals and saw the problems up close, she decided, “How can I, as an ethical person, look away and pretend this problem is not there?”

So she and a banker friend, Holly Howard, started looking into the possibility of a school-based health clinic at Lincoln High, but they met a wall of skepticism. People said they were risking liability.

“We as parents can’t be afraid to do the right thing,” she said. “We can’t be afraid of liability.”

Kirby and Howard convinced the school board to agree to a compromise plan. The clinic would not be located inside Lincoln High School; it would work out of a dilapidated old apartment building next to the school. Howard became the clinic’s first director.

At first, Kirby said, kids would come to the clinic with any excuse of an ailment—just to get away from school. But because the students were treated professionally, the value of the clinic began to sink in. In addition, the clinic’s mental health counselors started up girls’ and boys’ groups, which met for pizza at the clinic over lunchtime.

“Pretty soon we were seeing hundreds of kids,” Kirby said. The staff saw shocking cases, such as a girl who came to them with back pain. The girl had answered an online invitation from a stranger to travel 60 miles away to live with him as her “father figure.” He whipped her with a stick, a punishment called “caning.”

Kirby also said they would see kids who did their own tattoos because they weren’t 18, but the tattoos would get infected. “The kids would buy the ink and needles online and then share them. They’d get hepatitis as a consequence.”

Although the clinic began with physical needs at the forefront, it soon became clear that most of their resources would be focused on mental health.

“When kids got expelled, instead of saying, ‘What’s wrong with you?’, we started asking, ‘What happened to you?’” she said. “Kids would answer, ‘My uncle shot himself’ or ‘My mom’s new boyfriend beat her up and the police were there.’ The kids try to sit in their desk and do math, but they’re on constant alert, waiting for the next bad thing to happen. They have PTSD.”

The community began to take notice of the health clinic’s benefits when student suspensions dramatically dropped. Instead of hundreds of kids being suspended, the number went down to a dozen or so. But as students became healthier, some of them got pushback from their families, who told them, “You think you’re too good for us. You’re such a princess. You can’t live at home anymore.”

“We’d tell these kids it’s like they’re parachuting out of a burning plane, and their family is still on the burning plane, and they’re going in for a crash landing,” Kirby said. “You may want to try to get back on that plane, but you can’t.”

The health center was so successful that the original building was replaced with “the Hub”—a beautiful new structure that contained the Lincoln Health Center, a shelter for homeless teenagers, and a Headstart preschool. The model of school-based health centers also expanded to other schools in Walla Walla, including elementary schools, a middle school, and the main high school.

Kirby has been dealing with slow-advancing multiple sclerosis since 2000, and eventually the combination of her medical practice and volunteer work with the clinic took its toll. So, she retired in 2016, concentrating on her Master Gardener work—a fitting metaphor for the seeds she planted through the clinic in Walla Walla.

When the clinic first began in the rundown apartment next to Lincoln High School, she planted sunflowers in front. These were beautiful, unpretentious flowers that can grow in the toughest environment—like the kids.

“People would sometimes ask me why I am spending so much time on these kids,” Kirby said. “But there is no such thing as a throwaway kid. We heal their wounds.”