Several weeks ago, as the COVID-19 pandemic was spreading, Ying Diao, professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering, and her research group, including several graduate students, began thinking about how they could help fight the outbreak.

Through an inspiring NPR story, Diao learned about the creation of 3D-printed ventilator parts in Italy. She immediately realized that her lab could potentially make facemasks and parts for medical supplies through their collective expertise in 3D printing (creating three-dimensional objects from a computer aided design models) and fabrication.

“I quickly found YouTube videos from 3D printing enthusiasts that have put up facemask designs using low cost, accessible materials,” Diao said. “So I picked the brain of my students on this idea and challenged my group to take this into action.”

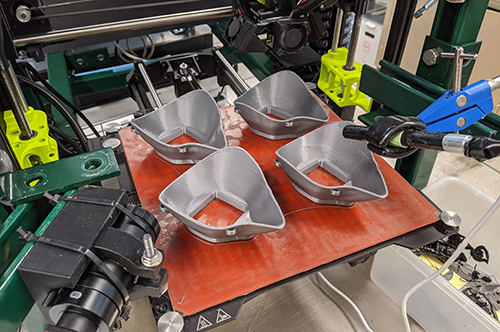

Diao’s research group adopted the Montana Mask design, a 3D printable and reusable filtration mask with design files that are free for public use. The group has optimized its laboratory 3D printers to make 10 Montana Masks per day, with its goal to fabricate, assemble, and donate hundreds of masks to healthcare workers facing dire supply shortages.

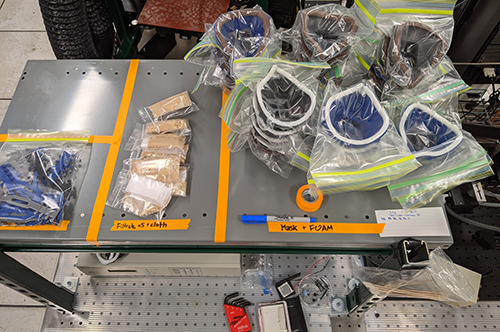

They’ve already made an impact. The group just sent out its first shipment of 70 masks; 20 went to the Monticello Police Department and the Piatt County Sheriff’s Department, and 50 went to Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas, Texas. The group established Champaign County Covid Relief, where people can find updates, protocols, and links for resources to make their own printed or sewn masks.

They are still seeking recipients for masks that they’ve made, and they encourage healthcare workers and emergency first responders to contact them at cccovidrelief@gmail.com.

Along with Diao, the task force includes graduate students Bijal Patel, Prapti Kafle, Daniel Davies, and Zhuang Xu. All students are volunteering their time to create the masks, and Patel, the project lead, is running the two lab 3D printers for printing the Montana Masks and filter cartridges.

The Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering donated $1,000 to help print the masks, and the group gratefully acknowledges support from Lori Sage-Karlson, a receiving manager in the School of Chemical Sciences, Jadii Rogers, a departmental assistant in the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, and others for their assistance in shipping masks, communicating with end users, and maintaining lab space during the pandemic.

{"preview_thumbnail":"/sites/default/files/styles/video_embed_wysiwyg_preview/public/video_thumbnails/NK4817kgGxE.jpg?itok=kfofAGlp","video_url":"https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NK4817kgGxE","settings":{"responsive":1,"width":"700","height":"394","autoplay":0},"settings_summary":["Embedded Video (Responsive)."]}

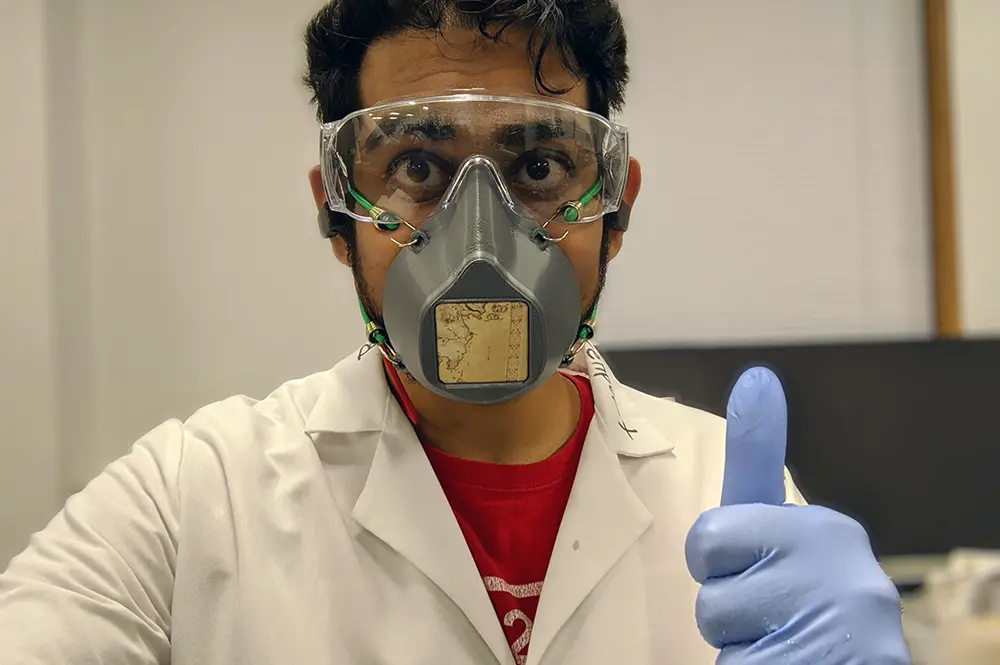

Patel has been working heavily on 3D printing for his normal graduate research, so assembling the masks is fairly straightforward for him. Every 12 hours, he gathers what’s been printed, checks them, and hands them off to the assembly team. Then he starts a new set.

After printing the masks, the group sands them down for smoothness, scrubs them with soap and water, and sanitizes them in a bleach solution. Then, the assembly team attaches rubber weather stripping to form a seal, and adds elastic, filters, and other accessories before packaging them for shipment.

Kafle’s role in the mask production includes disinfecting, assembling components, and packaging. After sanding the masks and disinfecting them in bleach, she inserts the filter holder and strap and disinfects the parts again. The mask includes a furnace filter and a simple cloth filter.

The process of disinfecting and assembling the masks feels like performing an experiment, Kafle said. When she was given the opportunity to contribute to the effort, Kafle said she wanted to join in.

“When my advisor brought up the idea of using the equipment in our lab plus our skills and time to make the masks, I immediately wanted to be a part of it,” she said. “I had read numerous news about the shortage of masks among healthcare workers and that thousands of them across the globe are getting COVID-19.”

Along with Kafle, Davies also works on prototyping the designs and coming up with ways to make them better and more comfortable. The group recently received some elastic for tying on the masks; Davies said that it was easy to investigate which designs would fit their parameters because the 3D printing community is quite open and sharing.

“Since our lab is currently shut down for regular work, we had extra time to spend on new projects like this,” he said. “I have my own 3D printer at home, so I thought it would be a good idea to at least make masks for ourselves and family members, and it made prototyping pretty easy.”

The lab uses two 3D printers for producing optical and electronic materials.

“Initially what we were seeing was that it would be difficult to actually make PPE to the standards necessary to keep health care workers safe,” Davies said. “But the Montana mask seemed to be the best option. From there, Bijal worked with the local hospitals to make sure they were usable, and we have been making adjustments to make our masks as effective as possible."

Patel said he’s been frustrated by the reported shortages of personal protective equipment for healthcare workers.

“Running this project and doing the best we can to help healthcare workers is a way to turn that frustration into something productive,” he said.