(Photo by L. Brian Stauffer)

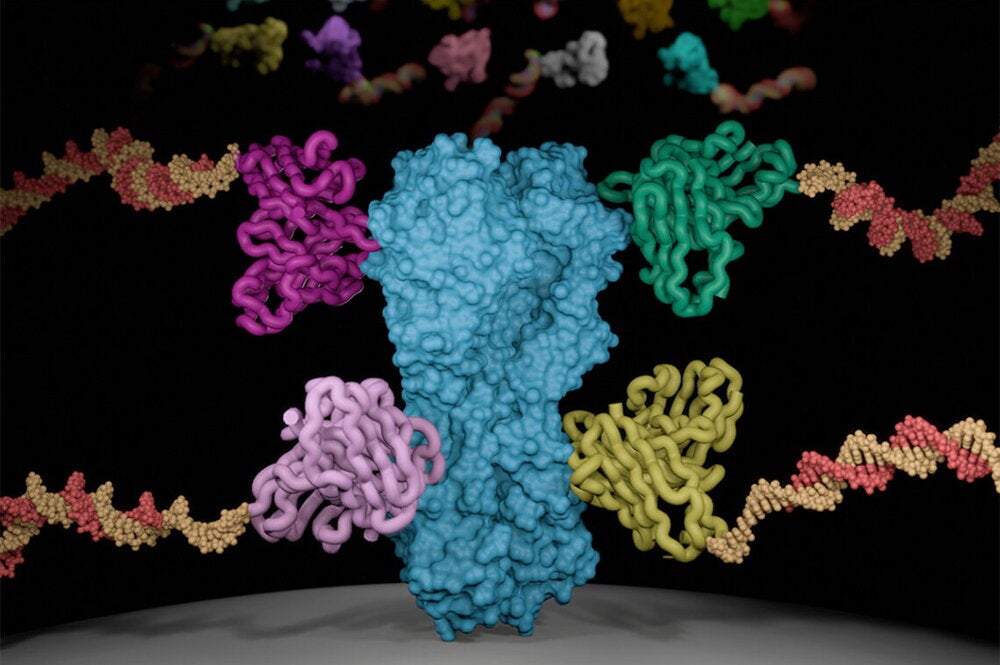

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to spread, scientists and health care providers are seeking ways to keep the coronavirus from infecting tissues once they’re exposed. A new study suggests luring the virus with a decoy – an engineered, free-floating receptor protein – that binds the virus and blocks infection.

Erik Procko, a professor of biochemistry at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, led the study, published in the journal Science.

To infect a human cell, a virus must first bind to a receptor protein on the surface of the cell. SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, binds to a receptor called ACE2, which plays a number of roles in regulating blood pressure, blood volume, and inflammation. It is found in tissues throughout the body, but especially in the lungs, heart, arteries, kidneys and intestines. Many researchers hypothesize that the host of symptoms associated with COVID-19 may stem from the coronavirus binding to ACE2 and keeping it from doing its job.

“Administering a decoy based on ACE2 might not only neutralize infection, but also may have the additional benefit of rescuing lost ACE2 activity and directly treating aspects of COVID-19,” Procko said.

As a potential therapeutic agent, a decoy receptor has one advantage over other drugs: To evade it, the virus would have to mutate in a way that would make it less infectious.

“A benefit of a decoy receptor is that it closely resembles the natural receptor. Therefore, the virus cannot easily adapt to escape neutralization without simultaneously losing its ability to bind to its natural receptor. This means the virus has limited ability to acquire resistance,” Procko said.

Although ACE2 binds to SARS-CoV-2, it is not optimized for that purpose, which means that subtle mutations to the receptor could make it bind more strongly. This makes it an ideal candidate for a decoy receptor, Procko said.

Procko examined more than 2,000 ACE2 mutations and created cells with the mutant receptors on their surfaces. By analyzing how these interacted with the coronavirus, he found a combination of three mutations that made a receptor that bound to the virus 50 times more strongly, making it a much more attractive target for the virus.

Procko then made a soluble version of the engineered receptor. Detached from cells, the soluble receptor is suspended in solution and free to interact with the virus as a decoy receptor.

After Procko posted his findings to a preprint server, a colleague connected him with the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases. Researchers there, along with the lab of Illinois biochemistry professor David Kranz, verified the strong affinity between the virus and the decoy receptor, rivaling the best antibodies identified to date, Procko said. Furthermore, they found that the decoy receptor not only binds to the virus in live tissue cultures, it effectively neutralizes it, preventing cells from becoming infected.

Further work is required to determine whether the decoy receptors could be an effective treatment of or preventive agent against COVID-19.

“We are testing whether the decoy receptor is safe and stable in mice, and if successful, we then hope to show treatment of disease in animals. Hopefully that data can facilitate a clinical trial,” Procko said. He also is exploring how the decoy receptor bonds to other coronaviruses with potential to become future pandemics if they cross from bats to humans.

The National Institutes of Health supported this work.