The story of Leo Koch is best understood in a 1960 frame of mind. That year, John F. Kennedy was running for president and Westerns such as Gunsmoke and Wagon Trail were the top shows on television. The eventual hit song “I’m sorry” was stalled in studios over concerns that the singer, Brenda Lee, was singing about love in a way unbecoming of a 15-year-old.

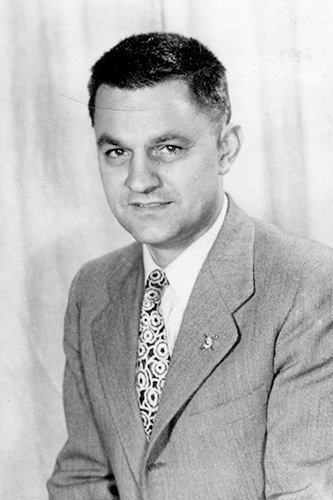

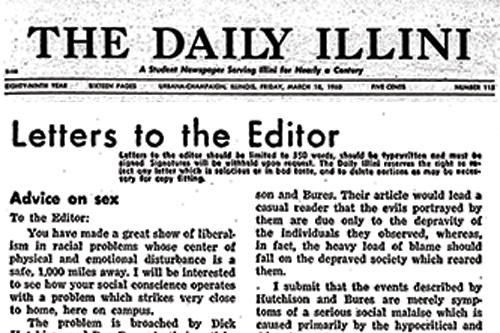

On March 18, 1960, the presses rolled at the Daily Illini, as usual. Its normal circulation in those days was only about 2,000, but its readership was higher that day as thousands of visitors were on campus for the start of the high school boys’ state basketball tournament being played at the Armory and Huff Gym. Those who opened the newspaper saw a letter to the editor from Koch, a professor of plant biology. It bore the headline, “Advice on sex.”

Koch, responding to a student column lamenting 1 a.m. curfews, blamed a “serious social malaise” on campus caused by “hypocritical and downright inhumane moral standards engendered by a Christian code of ethics which was decrepit in the days of Queen Victoria.”

“With modern contraceptives and medical advice readily available at the nearest drugstore, or at least a family physician, there is no valid reason why sexual intercourse should not be condoned among those sufficiently mature to engage in it without social consequences and without violating their own codes of morality and ethics,” Koch wrote.

By April, Koch was fired and a national debate over morality and academic freedom ensued. The American Association of University Professors censured the U of I, and student protests against Koch’s dismissal erupted from Illinois to Iowa and California. U of I President David Dodds Henry was hung in effigy in front of the U of I YMCA.

Letters for and against Koch poured in from 30 states and as far away as Norway. Newspaper editorial writers weighed in; the Harvard Crimson called Koch’s firing “misplaced Victorianism” while the Chicago Sun-Times cited a letter by the Rev. James Hine, pastor and director of the McKinley Foundation at U of I, who called Koch’s letter “the grossest oversimplification of facts and inadequate of a complex and important aspect of human existence I’ve ever had the agony to read.”

The fact that Koch, hired in 1955, was not yet tenured made it easier for the university to dismiss him. In a letter explaining his decision, President Henry called Koch’s actions “contrary to the commonly accepted standards of morality.” A July 1960 letter signed by 229 U of I faculty members, however, objected to the phrase.

“By including this charge, rather than judging the case strictly in terms of the professional responsibility displayed by Prof. Koch, the Board of Trustees has set a precedent that infringes on free inquiry, teaching, and discussion,” the letter stated.

Koch took his case to court but lost, ultimately being denied hearings by both the Illinois Supreme Court and the U.S. Supreme Court. Thus ended the tenure of Leo Koch at U of I, but in the wake of his dismissal the university began revising policies for removing faculty, according to Matthew C. Ehrlich's book “Dangerous Ideas on Campus: Sex, Conspiracy, and Academic Freedom in the Age of JFK.”

These new policies were put to the test a short time later when, in 1964, U of I classics professor Revilo P. Oliver harshly criticized President John Kennedy in the pages of American Opinion just a couple of months after Kennedy’s assassination.

Faced with another professorial controversy, President Henry this time turned to the faculty senate for their opinion, according to Time magazine.

While the senate made clear it didn’t support Oliver’s views, it defended his right to state them. Henry recommended that Oliver be allowed to keep his position; the Board of Trustees overwhelmingly agreed.

By then Koch was long gone. He landed a position at Blake College, a small liberal arts school on the outskirts of Mexico City, where he edited Mushroom Digest, a bulletin on growing mushrooms, according to the Daily Illini. Later he co-founded the Sexual Freedom League in New York City. He died in the early 1980s.

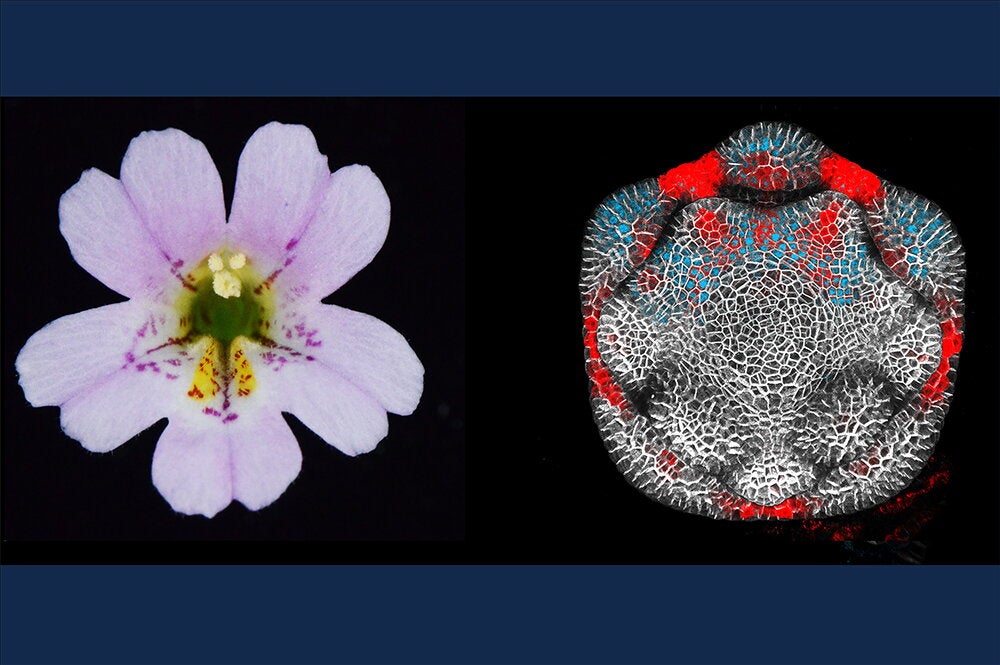

Koch is remembered a little differently among plant biologists. When he left the U of I, he left behind all his plant research, including an incredible collection of more than 8,000 plant samples.

It turns out that Koch was a renowned collector of mosses, liverworts, and hornworts. The University of Illinois Herbarium is still in the process of cataloguing them. David Seigler, a professor emeritus of plant biology who arrived at U of I after Koch, said that with help from experts around the country they’ve identified much of Koch’s collection, but that a third of Koch’s liverworts and hornworts hasn’t yet been identified.

Koch collected samples on his own time from sites in California and the southeast United States, Seigler said. He also exchanged samples with researchers in Japan and Europe.

“He was considered by the other bryologists to be one of the leading people at the time,” Seigler said. “Anyone in that field would still know about his collections. They were excellent. There are not many people who can identify them.”

Koch may have been a little better at plant collecting than other responsibilities. According to university records, he was informed in 1959, months before he wrote his letter, that his contract would end in 1961. For all the lasting furor over his letter, it cut short his time on campus by only a year.

Editor's note: This story first appeared in the Fall 2022 issue of The Quadrangle.