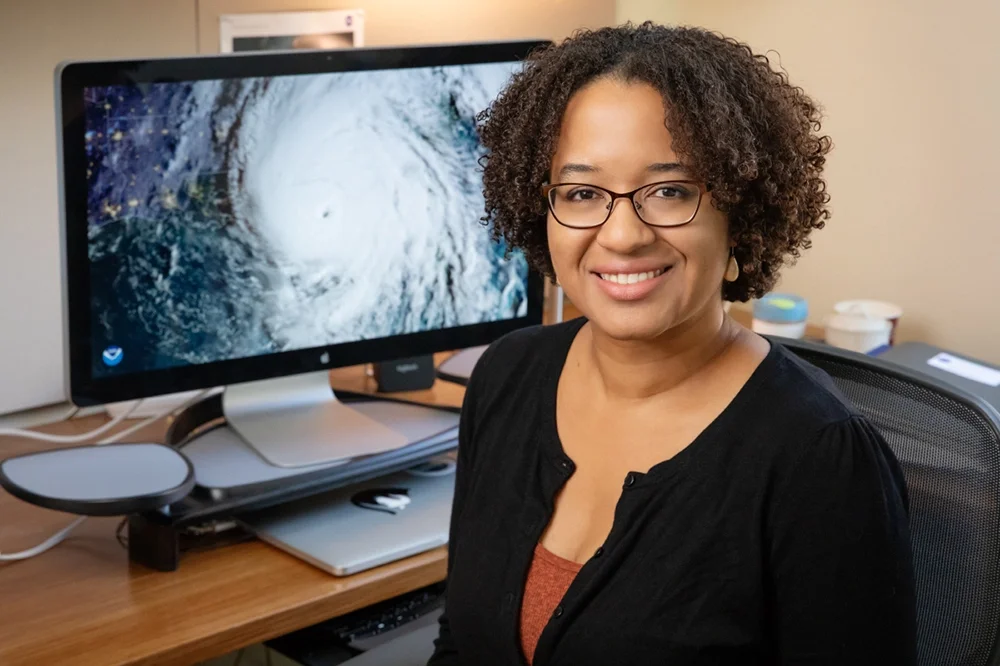

Hilary was the first tropical storm to hit California in 84 years. Atmospheric sciences professor Deanna Hence spoke with News Bureau physical sciences editor Lois Yoksoulian about what made this storm unique and if the Southwest U.S. should expect more like it in the future.

Why don’t we usually see tropical cyclones along the western coast of the U.S.?

One of the biggest reasons we don’t see tropical cyclones along the western coast of the U.S. is because these storms generally need warm water to get the energy to survive. Unlike the eastern coast and Gulf of Mexico, which have warm water currents close to land, the western coast has a current bringing cold water from the North Pacific towards the equator. There’s also a lot of cold water outside the equatorial region because cold water from the deep ocean is being pulled upwards just offshore of North and South America. These cold waters mean that if a tropical cyclone wanders away from the tropical regions towards the Baja peninsula of Mexico or California, it quickly finds itself over cold water and loses access to that energy. Sometimes, a storm is strong enough to survive anyway, but it becomes more difficult the further it travels over those cold waters.

Another big reason why we typically do not see these types of storms along the western coast is because tropical cyclones are steered mainly by the flow of the winds around them. Tropical cyclones typically form in the east-to-west wind belt close to the equator, known as the trade winds, and so in their early days, they often track toward the west. Over time, their tracks tend to move more toward the north, and if they get far enough north, they get caught in the west-to-east winds of the mid-latitudes and start moving more toward the east. For the East Coast, the initially westward motion moves the storm closer to North America, and how rapidly the storm “recurves,” or turns more northward and then eastward, will determine whether the storm stays out to sea, hits the East Coast, or hits the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico.

It’s the opposite case for the West Coast; if the storm recurves quickly, it will be better positioned to hit Mexico or the U.S. West Coast, but more likely the storm will be taken westward, far away from land. Combine that distance with the fact that in the eastern Pacific Ocean, that northward movement moves the storm over cold water much more quickly than it does in the northern Atlantic Ocean, and it typically makes it difficult for storms to make it to the U.S. western coast.

What are the conditions that spawned Hilary’s path?

How warm or cold the waters are near the equator has a lot to do with changes in atmospheric and oceanic circulation patterns and swings every few years from warmer to colder in a pattern known as the El Niño southern oscillation. The phase where those waters are warmer than usual, known as an El Niño, means that warmer water is available over a much bigger area of the equatorial eastern Pacific than usual, which has been the case this summer. That gives a more extensive area for a budding tropical cyclone to get energy from, especially when combined with warmer-than-normal ocean temperatures off the coast of California. This warmer water allows a hurricane to make it further north without losing as much energy.

In addition, the big high-pressure “heat dome” that has positioned itself over the Southwest and central part of the country is directing the atmospheric flow pretty much straight north and northeast, which would guide a budding tropical cyclone more toward Mexico and California. This combination of conditions is not unheard of, but their timing and severity are unusual.

Should the U.S. Southwest expect to experience more storms like Hilary in the future?

This is a difficult question to answer, given that there are numerous factors to consider when discussing a) when and where a tropical cyclone forms; b) whether it will make landfall somewhere it can cause damage; and c) how strong it will be if it does so and what kind of impact will it have. Climate change’s effects on atmospheric and oceanic circulations and storm processes can influence all three factors. However, human decision-making also dramatically influences who and what is in harm’s way when such events happen, which is an important and intertwined issue when discussing impact.

Experts say it is too early to assert that climate change is responsible for Hilary, but do you expect scientists to come to that conclusion eventually?

When it comes to storms like Hilary, figuring out climate change’s role requires teasing out what, if any, portions of the puzzle climate change may have made more likely to happen. Given the numerous pieces involved, I expect an “it’s complicated” type of answer because the number of things that have to come together to make a hurricane happen, let alone make landfall, is itself complicated. But I assure you that each of these pieces, and how they came together, will get intense and careful scrutiny.