Note: Watch a video about how researchers are examining coal balls to learn about the ancient past.

Paleobotanists at the University of Illinois understand one thing better than perhaps anyone in the world: Studying coal balls is a long-term commitment. The late plant biologist Tom Phillips began hauling the prehistoric objects out of the ground more than a half-century ago and filled a warehouse with tens of thousands of them. He passed away in 2018, but the coal balls have revealed only a tiny fraction of their insights into ancient Earth.

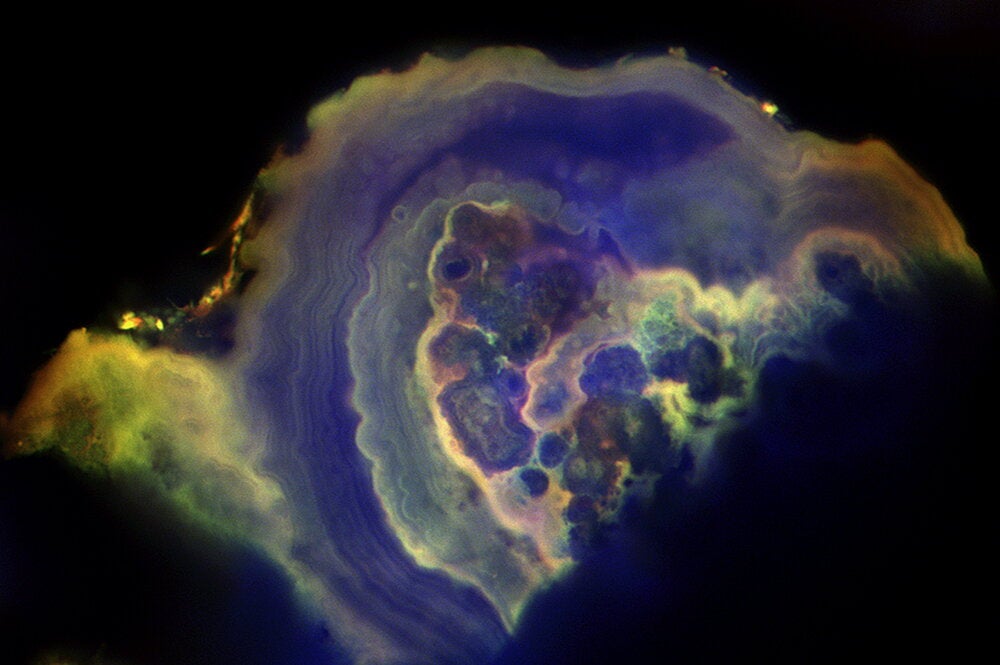

This is when most people ask, “What’s a coal ball?” To the untrained eye they would appear to be a regular old rock. If you sawed them open, however, you’d gain a perfectly preserved window into what plants used to be like 300 million years ago, from the spores and leaves down to the cell structure.

Thanks to a gift, U of I’s massive coal ball collection, the largest in the world, will continue to be researched. Michael (MS, ’02, Earth science and environmental change) and Lalana Fortwengler have helped create the Tom L. Phillips Memorial Fund for Paleobotany.

According to the School of Integrative Biology, the fund has so far supported a dozen graduate and undergraduate students conducting paleobotanical research. The fund is supporting the development of an image analysis platform, so that the collection can be made digitally available to paleobotanists around the world.

Surangi Punyasena, a professor of plant biology, said coal balls are found primarily in coal seams in the central United States and parts of Europe and China. They were formed during the Late Carboniferous and Early Permian ages, when the chemical conditions of the environment (much of Illinois and the Midwest resembled the Florida Everglades at that time) allowed for exceptional preservation of plants.

“Coal balls perfectly preserve a window into what plants used to be like 300 million years ago.’’

The plant life of that age would have resembled alien forests today, Punyasena said. Today’s spore-bearing plants are tiny, such as ferns, but back then they were as large as trees. The plants and surrounding environment are preserved in the coal balls.

Scott Lakeram, a graduate student in plant biology, said that he grew up in awe of dinosaurs and prehistoric life. “Every kid wants to be a paleontologist,” he said. He earned his undergraduate degree at Texas A&M University and came to U of I for graduate school for the enormous coal ball collection.

Lakeram studies the interactions of prehistoric bugs with plants of that period. Doing so requires obtaining high resolution images of the interior of the coal balls; this is done by sawing open the coal balls and polishing the exposed surfaces so that a thin layer of the ancient plant cells and other material can be lifted onto cellulose acetate paper. These “peels” are studied closely by scientists.

It’s a process that Tom Phillips created and others have developed. To date, U of I researchers throughout the decades have created more than 250,000 coal ball peels. Part of Lakeram’s work is digitizing high-magnification images of them.

“The point of digitizing the peels is (to) eventually create an artificial intelligence to automate the identification of the plant contents within these balls,” he said.

There’s plenty of time for learning new methods. Punyasena said that the immense size of the collection

is part of its legacy.

“I don't think that we will ever be done analyzing this material,” she said. “It is not just the scale of the material that's interesting or important, but the fact that each generation of researchers can bring new questions, new techniques to the collection. The beauty of the collection is that its utility never goes away.”

Scott Elrick, head of the bedrock geology section at the Illinois State Geological Survey and one of the co-curators of the collection, worked with Tom Phillips for several years prior to his death. As he stands in the coal ball warehouse, surrounded by rows of tall shelves and dusty boxes, it’s hard not to reflect on the incredible passage of time—both conceivable and not—represented within the space.

“In my conversations with Tom in his later years, he said that in some respects he was more of a curator than he was a scientist,” Elrick said. It’s a sentiment that hardly anyone agrees with, including the National Academy of Sciences, which made Phillips a member in 1999. As Elrick notes, the collection is about more than the answers it’s provided. It’s a scientific laboratory for the ages.

“There’s easily 50,000 individual coal balls here,” he said. “What are the opportunities that are sitting here? What do you know and what don't you know? And how do you know what you don't know?”

Elrick smiled widely at the thought.

Editor's note: This story originally appeared in the Fall 2023 issue of The Quadrangle.