Bobby J. Smith II remembers the day that changed his professional life. He was a graduate student at Cornell University when he began to read “I’ve Got the Light of Freedom,” a seminal study of the community organizing tradition in the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi and across the South, by Charles Payne. On page 158 he read the lines that altered the arc of his career.

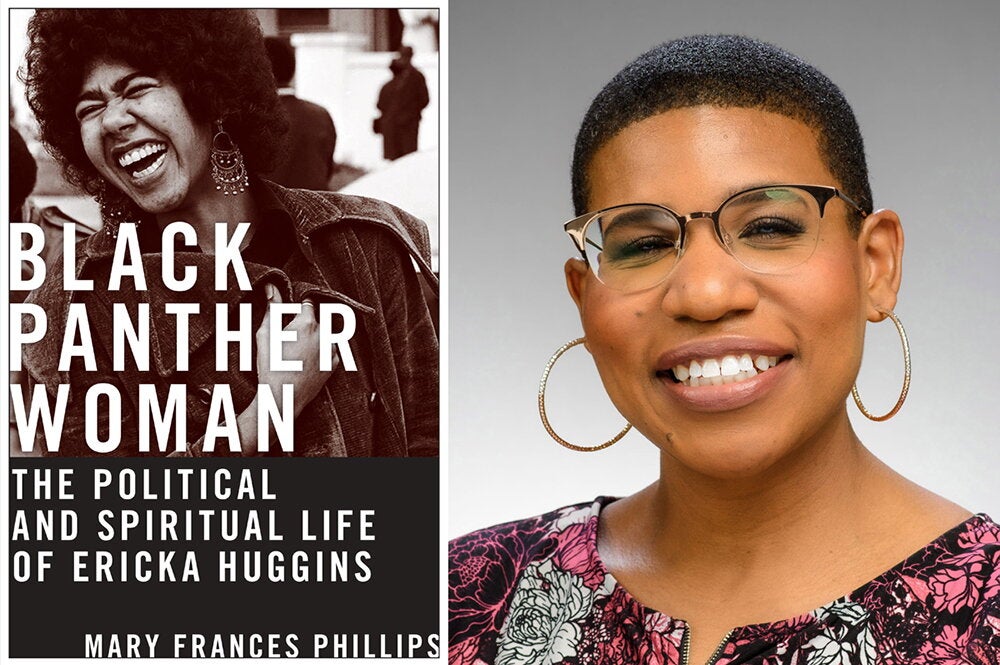

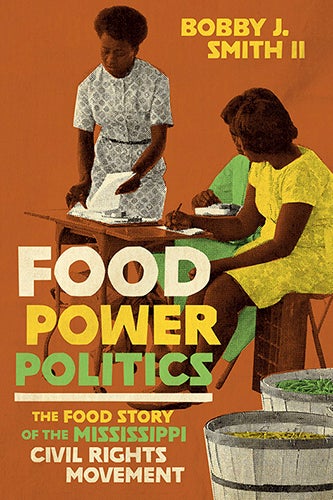

Now, a few years later, Smith, a professor of African American studies, has published “Food Power Politics: The Food Story of the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement,” the inaugural title in the Black Food Justice series by the University of North Carolina Press. Fellowships from both the National Endowment for the Humanities and the American Council of Learned Societies gave him the time he needed to finish an exploration of how one of life’s basic necessities—food—was manipulated to maintain power structures—and how African American communities responded.

What is your book about?

In my research, I seek to understand how African American life can help us understand food and agriculture, particularly across the United States. Also I'm interested in understanding how food and agriculture can then help us understand the African American experience. Essentially the civil rights movement in Mississippi was a quintessential example of how food was used as a weapon against African Americans and then how they responded to that, creating their own food programs and systems. The book is really just trying to help us rethink how we think about food. It’s not just something on our plate or something we get at the grocery store. In fact, food, when put into certain hands, could actually marginalize people or make them more food insecure.

What did that look like in Mississippi?

It was used as a political weapon by taking away access to a federal food program. There was a program called the Federal Surplus Commodities Program. Many people might know it as government cheese, or government peanut butter, where the federal government would give out free non-perishable goods, typically to poor people. It was a big program for particularly poor rural Black people who were sharecroppers in Mississippi. And in 1962 in Greenwood, Mississippi, the Leflore County board of supervisors actually dismantled the free food program as a form of voter suppression. In response, activists organized their own multi-state food program that brought thousands of pounds of food into Mississippi. It was a way to address voter suppression but it also was a catalyst for one of the largest voter registration efforts across the South at the time.

Food was also an economic weapon. I talk about how grocery stores, particularly white grocery store owners, would use the federal food stamp program as not only a way not to feed people, but also as a way to make profit. I argue that the federal food stamp program wasn't designed solely to feed people. There was a part of it that was designed to ensure that commercial food outlets could make profit. And in Mississippi the profit outweighed people's abilities to get food. Those communities responded by creating farm cooperatives, a network of grocery stores, and they also created multiple food programs. They controlled how food was produced, consumed, distributed and accessed. That was a crucial part of the civil rights movement.

When did you want to become a professor?

I knew that I wanted become a professor during my freshman year at Prairie View A&M University, a historically Black college in Texas. All of my professors were Black. Although I went to a predominantly white high school, going to a Black college wasn't necessarily a cultural shock or anything per se, but after seeing so many Black professors and how they carried themselves, I wanted to be like them. They were so smart. You could ask them any question in class and they would just rattle off the answer. I said, “I really want to be like you all.” They were so cool to me.

And I think about representation, because I didn't know I could be (a professor) until I saw that. I grew up around mostly Black doctors, Black engineers, Black medical professionals. So I thought that I was just going to go into that because they made a lot of money. But I saw (professors) and how they carried themselves, how they spoke, how they cared for students, how they were passionate about their research. My undergraduate degree is in agriculture, with a concentration in agricultural economics. I saw Black people talk about agriculture in that way, and it wasn't agriculture as oppression. It wasn't about slavery, it wasn't about backbreaking labor. It was about how to enhance the nation's largest industry, which is agriculture. And I remember one day I went into one of their offices and I was like, “How do I do this?” They said, “Here's what you do—get a PhD.” Thank God I followed it.

What was a life-changing moment for you?

Honestly I'm just super happy about the book. But I remember when I first got the idea for the book, I was in graduate school in the spring of 2016, and I had been doing some local activism surrounding food justice and Black Lives Matter at the time. I took a class called Community Development and Organizing. I read a book by Charles Payne called “I’ve Got the Light of Freedom.” As I was reading it, my professor at the time said, “When you read this book or read any book in this class, make sure you think about your project.” So I’m reading this civil rights book about Mississippi and food, and it’s (hundreds of) pages long. I’m reading and reading it, and there’s no food, no food, no food. Then, I’ll never forget, I read page 158. Page 158 is when food entered the conversation of that book. (Payne) didn’t say food was a weapon, but essentially the story characterized how food was weaponized politically against Black communities in Mississippi. I had never seen this before. And that one page (became) the foundation of my book project. That was seven years ago in graduate school. I was so excited. I was like, “I actually have a project now. I can actually do this.” And that took me into a whole different direction.

I met the author of the book two years later in spring 2018. He came to Cornell to give a talk about some different research he was doing. And I had to meet him, so I got a chance to go to lunch with him. I brought my book with me because I wanted him to sign it. He signed the book and I'll never forget. He wrote, “Bobby, thank you for telling the next part of the story.”

Editor's note: Read more LAS Experts profiles here.