A new book by rhetoric and history scholars examines the origins of critical race theory in legal studies. The movement is an area of legal scholarship that seeks to understand the relationship between race and racism and the law and other societal institutions in the U.S., the authors said. It is highly controversial, with politicians at all levels of government trying to ban it from classrooms.

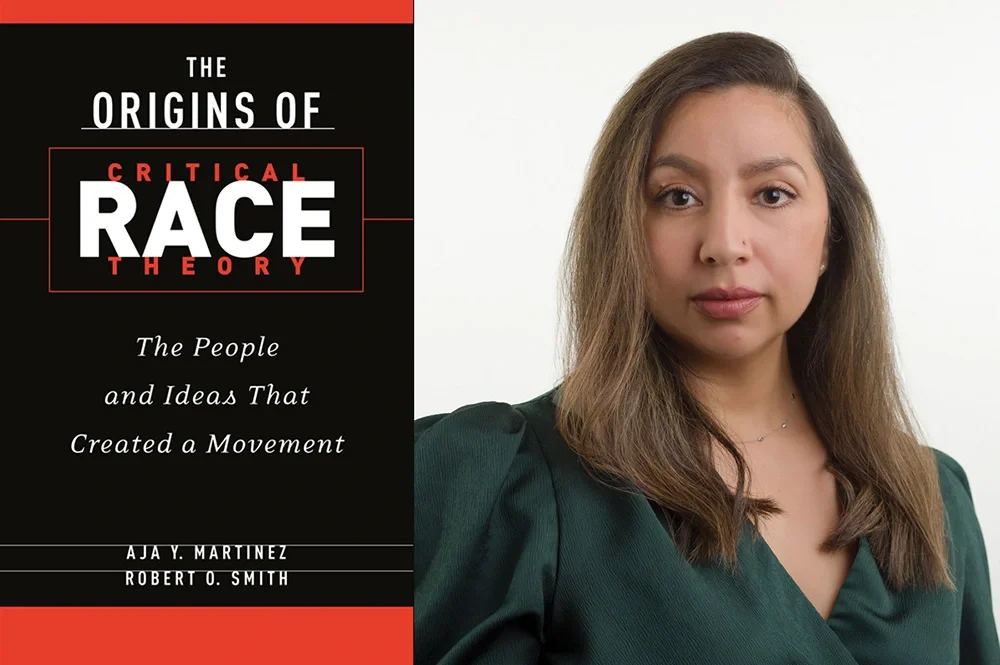

Both proponents and opponents of critical race theory often misunderstand what it means, said University of Illinois Latina/Latino studies professor Aja Martinez. She tells the story of what it is and how it was founded in her new book, “The Origins of Critical Race Theory: The People and Ideas that Created a Movement,” cowritten with Robert O. Smith, a history professor at the University of North Texas and Martinez’ writing partner and husband.

Martinez, who is a rhetoric and writing studies scholar and the author of the 2020 book “Counterstory: The Rhetoric and Writing of Critical Race Theory,” said she and Smith tried to make the history of critical race theory accessible by using a storytelling style of writing.

The use of “counterstory” is a key methodology of critical race theory, and it provides perspectives that have been ignored by the legal establishment and society, they wrote.

“The power of CRT is in stories — stories that humanize data, that communicate truths,” Martinez and Smith wrote. “Storytelling has the power to make those perspectives heard so dominant classes can no longer avoid the responsibility of listening.”

But academics are not communicating effectively about what critical race theory is, and they often are exclusionary in talking about it, they said. Meanwhile, its critics have “largely succeeded in framing CRT as a monster, a villain, the boogeyman waiting for your children at school. It was a manufactured sociopolitical crisis intended to stir up the masses, create havoc and confusion, and promote intentionally deceptive definitions, terms, and concepts,” they wrote.

Martinez said the book aims to accurately report the history of the theory and to humanize it.

“The idea that eventually became CRT was always about people and their relationships,” she and Smith wrote.

The theory is concerned with how inequality and racism are embedded in society. It is a critique of how the concepts of freedom, equality and equal opportunity work, or don’t work, and it is based on people’s lived experiences, Martinez said.

The tenets of critical race theory include racial realism or recognizing and working from circumstances as they exist; a commitment to social justice; the centrality of the experiences, knowledge and voices of people of color; and interest convergence, which is the belief that progress on the rights of marginalized people only happens when those actions also benefit the privileged.

The storytelling aspect of critical race theory started with one of its founders, the legal scholar Derrick Bell, who used legal storytelling to transform academic arguments and legal insights into ideas that were accessible to the public, the authors wrote.

They explored the archive of Bell’s papers at New York University and conducted interviews and oral histories with legal scholars Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic, who founded the movement along with Bell, and with others who had worked with Bell. The book examines Bell’s career as an NAACP Legal Defense Fund lawyer who worked on school desegregation in the 1960s and as the first tenured Black law professor at Harvard University. Martinez and Smith trace how he was influenced by civil rights leaders Medgar Evers, Thurgood Marshall and Martin Luther King Jr.

In addition to the individuals who formally established critical race theory as a discipline in 1989, the authors examine the events that advanced the movement, including Bell leaving Harvard in protest over the lack of hiring of Black faculty members, the discontinuation of a civil rights course he taught there and a student protest over the loss of the course.

Martinez said that critical race theory is an outgrowth of the Civil Rights Movement, but its roots go back even further, to the thinking of Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth and W.E.B. Du Bois. She said those foundations for the legal theory refute the notion that it is somehow anti-American or a European Marxist idea.

“The story of CRT is a quintessentially an American story; the movement’s deep roots are intertwined with key figures and flashpoints of U.S. history at every twist and turn of its development,” she and Smith wrote.

They also dispute the idea that the theory is divisive.

“It informs the work of some educators, but in ways that are about equity in education. Are we giving students the same experiences, and if not, how can we collect data from their stories to do better by them? Are their stories missing from the curricula?” Martinez said.

She said critical race theory often is conflated with diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives, but while they at times overlap, they are not the same thing. Critical race theory is a critique of how the ideas of liberalism function in institutions, while diversity, equity and inclusion focuses on compliance with mandates for equality, she said.

Martinez and Smith will speak about the book at a book launch event on April 15 at 4 p.m. at the Illini Union Bookstore, 809 S. Wright St., Champaign.