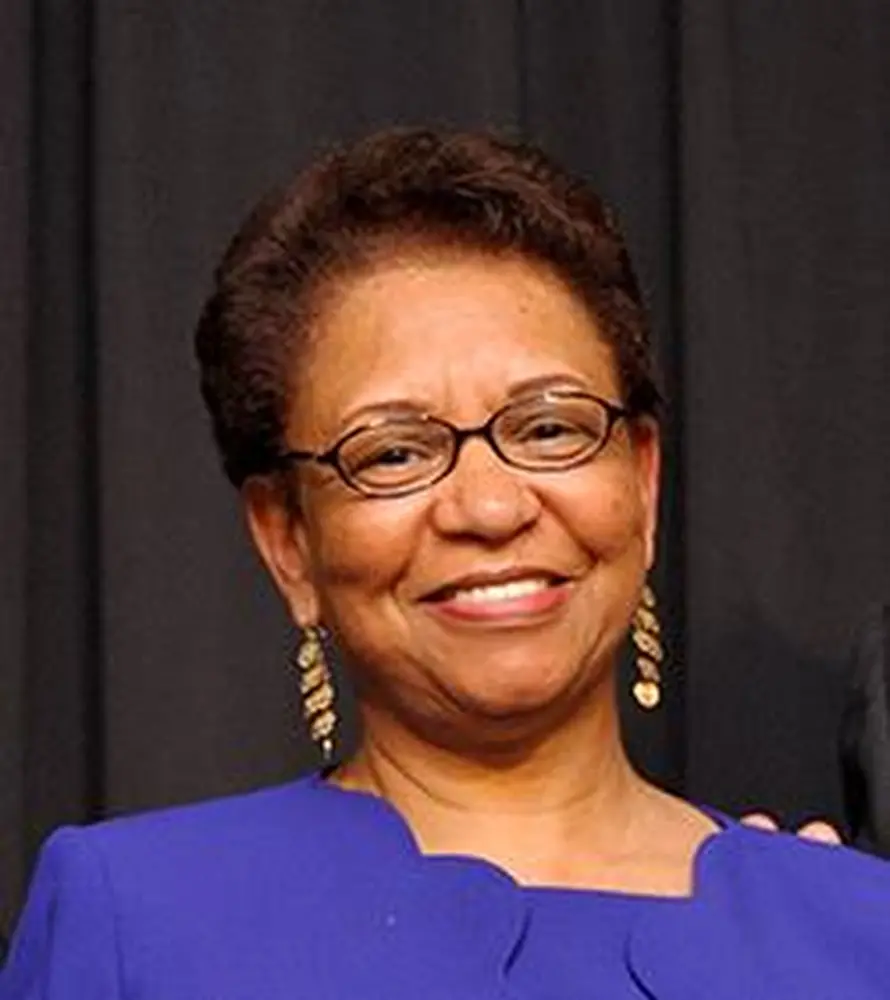

Edna Greene Medford will never forget the eerie feeling that crept over her when she was driving down the long, narrow road leading to the Westover Plantation in Virginia in the mid 1990s. It was night, and the trees on both sides of the dirt road crowded in on her, she recalls.

“It made me think about the people who had lived and died on the plantation—people who had never seen freedom,” says Medford, an LAS alumna (MA ’76, history) and chairperson of the Department of History at Howard University. “Before that visit, the lives of slaves were academic to me. But driving up that lane that night made me connect with the people who had lived there.”

The connection remains to this day, for Medford has emerged as one of the country’s leading authorities on 19th-century African American history, Abraham Lincoln, and the Emancipation Proclamation. She is also a 2013 recipient of the LAS Alumni Achievement Award.

Medford grew up in Charles City County, Va., where the Westover plantation is located. In the 1960s, the school system in this rural county was split into three segregated parts—schools for white children, schools for African Americans, and schools for Native Americans.

The school system did not fully integrate until 1970, one year after Medford left high school, so she had no white classmates and no white teachers to that point. In fact, because she received her bachelor’s degree from Hampton Institute, a historically black college, she had very little contact with white students until she came to the University of Illinois in 1973.

“To say the least, it was culture shock,” Medford says, but not just because she suddenly found herself as a minority. Growing up in a rural area, she also wasn’t used to the sheer size of the campus. Medford came to Illinois because her husband was in law school, and she started out as a U of I employee. But she began taking classes on the side and enrolled in the master’s program in 1974.

After receiving her master’s degree in history in 1976, she went on to earn a PhD at the University of Maryland in 1987 and immediately began teaching at Howard University. Her specialty was 19th-century African American history, but an invitation from the C-SPAN television network in the mid-1990s suddenly sent her career in a surprising new direction—toward Abraham Lincoln. C-SPAN was filming reenactments of the Lincoln-Douglas debates, and the network asked her to do on-air commentaries and lead workshops for their staff to give them a sense of the time period.

“From there, my work on Lincoln took off, and I haven’t been able to move away from him ever since,” she says.

At the time, Medford says, she didn’t have a deep interest in Lincoln because she grew up when esteem for Lincoln was fading, particularly in the African American community. “People had been told forever that Lincoln freed the slaves because he cared so much from a humanitarian perspective, but once they found out that the story was much more complex, there was a diminishing of reverence for him.

“There is no question that Lincoln hated slavery,” she continues. But the core reason he issued the Emancipation Proclamation was military necessity; he hoped to create chaos in the South, which was dependent on African American labor.

However, she points out that the complicated motivations of Lincoln simply make him all the more intriguing. “We do him a disservice when we see him as an icon. I think he’s so much more interesting when we explore all of his complexity.”

Exploring the many facets of his personality is what Medford has been doing ever since the C-SPAN experience. She was awarded the Order of Lincoln Medallion in 2009, authored books and many papers on Lincoln, regularly participated in the History Channel’s Civil War Journal, and held leadership positions with the Lincoln Forum at Gettysburg, the Lincoln Bicentennial Foundation, the Lincoln Studies Center at Knox College, and the Abraham Lincoln Institute. She has also chaired the Scholars’ Advisory Council at Lincoln’s Cottage in Washington, D.C., been involved with the Abraham Lincoln Association in Bloomington, Ill., and spoken on the Emancipation Proclamation throughout the world, including Ireland and the Netherlands.

But her life hasn’t been Lincoln 24/7. In addition to being on the board of Border’s Bookstores for 12 years, she has served with National History Day, Inc., the Ulysses S. Grant Association, and the Association for the Study of African American Life and History. She is also a popular teacher, winning the Howard University Student Association’s Professor of the Year award in 2013.

Medford even directed the historical team studying the African Burial Grounds in New York—a large slave cemetery uncovered in the heart of Manhattan in the 1990s.

They found that colonial slavery in the North was every bit as severe as in the South. One skeleton, for example, showed that a slave woman’s face had been crushed, possibly by the butt of a rifle, her wrists had been broken, and a bullet was lodged in her chest.

“Whenever I go to a place where African Americans have suffered like that, I can feel it, and I think that’s true for anyone who studies this history,” Medford says. “I don’t know how you could not connect.”