Before Julia Cisneros started working toward her PhD in geology at the University of Illinois, our understanding of sand dunes on the bed of large rivers was limited, and based largely upon observations in small rivers and laboratory experiments.

After several years of research, however, Cisneros has developed a method that brings to light the characteristics of such dunes, which affect the movement of sediment and water, flooding, and habitats within the world’s biggest rivers.

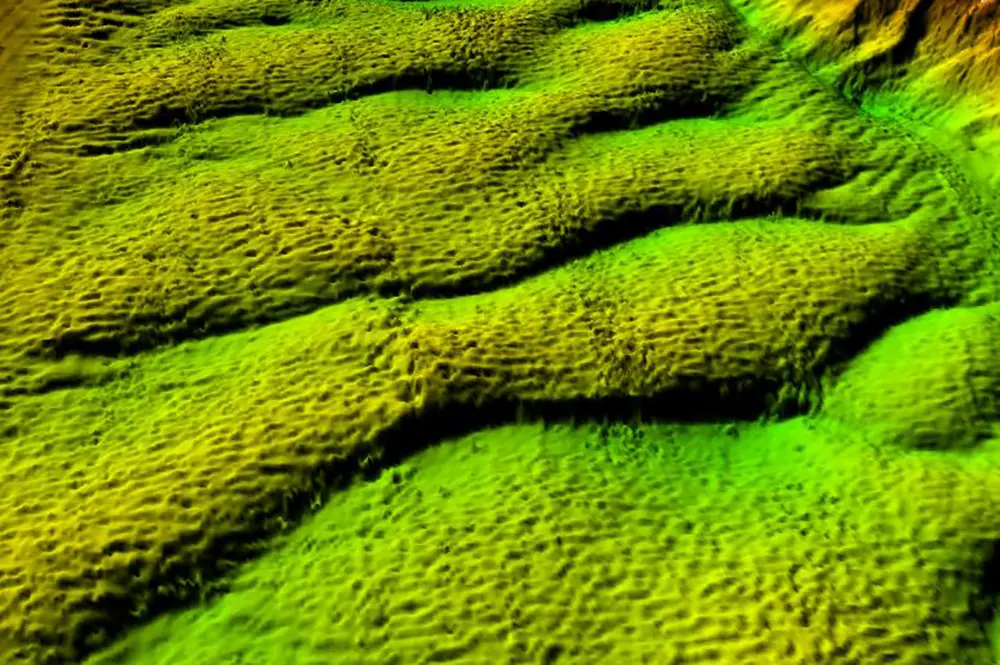

More specifically, Cisneros was interested in measuring dunes, which move across the riverbed and also create resistance to flow in rivers. While this wouldn’t be the first time river dunes have been studied, Cisneros wanted to expand knowledge of river dune influence in some of the largest rivers, such as the Amazon.

“I started this research because I just love dunes,” Cisneros said. “So during my undergrad I studied desert dunes, and then I wanted to study dunes again.” She discovered Jim Best, the Jack and Richard Threet Professor of Sedimentary Geology at Illinois, who is a global authority on river dunes and study of the world’s big rivers.

Cisneros started working on this project in 2015. Using multibeam echo sounder (MBES) data available through Best’s past research and network of collaborators across the globe, she studied five large rivers—the Amazon, Mekong, Mississippi, Missouri, Paraná—and a smaller one, the River Waal, in the Netherlands.

Cisneros’s first challenge was to develop a more accurate and efficient method for quantifying the shape of such river dunes from these huge datasets—and the end product was the Bedform Analysis Method for Bathymetric Information, or BAMBI, which analyzes the entire spatial area of a river and measures the riverbed dunes across the river width. By using the analysis method and bathymetric data obtained via MBES in each river, Cisneros made possible a much fuller understanding of the shape of dunes in the world’s big rivers, and the application of this knowledge for contemporary channel management and interpretation of ancient riverine sediments. The findings are now published in Nature Geoscience.

Cisneros and Best are lead authors on the paper, which involved collaboration with scientists from the United States, U.K., Netherlands, Argentina, Brazil, and China.

“It's just completely ramped up the amount of information that we have on such river dunes,” Cisneros said.

Before BAMBI, scientists knew more about the surface of Mars than they did of the bottom of big rivers, Best said. But with rivers like the Amazon, which is up to 120 meters deep in places, riverbeds are often difficult to measure and understand.

“This technique (MBES) gives you an incredibly detailed map. It's basically like you drain the river completely of water without affecting anything, so you can reveal the smallest of features,” Best said. “So, once you've done that, then you can devise analytical methods in order to measure what the shape of the riverbed is.”

Since measuring these larger rivers, the researchers found that big river dunes tend to be flatter and possess lower slopes than those in smaller rivers, meaning that they also transport their sediment differently and affect the flow in a different manner.

“Improving our approach to modeling how modern rivers will change, and revealing what big rivers look like in the ancient rock record, demands that we take this new understanding of river dune shape into account. This is one of the biggest takeaways from the paper” Cisneros said.

Not only is the BAMBI method applicable to the largest rivers, it is also easy to use and works fast. The method can also be applied to understand dunes in many river environments, large or small.

“A lot of people have responded really positively and are really excited to use it,” Cisneros said. “I think it offers a universal way for people to understand dunes and analyze their shape and their size.”

As Cisneros is finishing up her last semester of graduate school, she is still working on making BAMBI more available for others to use. Cisneros will continue her research and fascination with dunes in a post-doctoral position in Texas after she earns her PhD, where she will continue studying river and desert dunes, and applying BAMBI.

“It's been a long time coming,” Cisneros said. “I've been working on the project since my first semester of graduate school.”