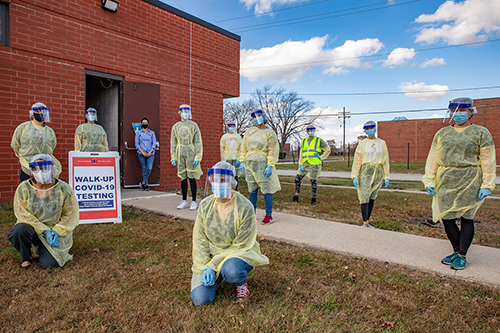

(Photo by Fred Zwicky.)

Workers at the Rantoul Foods pork-processing plant were among the first outbreak clusters when COVID-19 emerged in central Illinois in spring 2020. When researchers from the University of Illinois found no traces of the virus in air and surface samples at the plant, however, it raised questions about how the disease was being spread.

The university began working with clinicians and community researchers to provide pop-up testing clinics in Rantoul. An interdisciplinary team of LAS professors also began investigating the structural, economic, and sociocultural factors that impact transmission and response to the disease among essential agricultural laborers in rural communities.

“We wanted to understand more broadly how interaction in the community works, how people think of the working community, how people think of the virus, and how they think of protecting themselves or what risks they have to take given their need to work in an essential industry,” said Ellen Moodie, professor of anthropology who is an expert on Central America, human rights, and ethnographic research.

“Our goal is to understand how we can address questions of how to protect oneself, what are good public health practices, and how to mitigate the spread of the virus within particular communities,” she said.

Rantoul has offered unique insight into the ethnography and science of how the virus spread.

“Rantoul has a very diverse community and its industries recruit worldwide—in Africa and Central America as well as Puerto Rico—so they have workers who speak Spanish, Lingala, the Mayan language Q’anjob’al, and other languages,” said Gilberto Rosas, who is a professor of Latina/o studies and an expert on migration and violence along the U.S.-Mexico border.

Rantoul residents, in addition to being tested, were surveyed about behaviors and about living and working conditions associated with higher rates of infectious disease.

“The problem is, in this community and others there are many essential workers but not universal access to COVID-19 testing resources or response,” said Rachel Whitaker, professor of microbiology. “There’s generally not a lot of infrastructure for reaching these groups.”

The research may shed light on disparities in COVID-19 infection rates among various demographic groups, said Jessica Brinkworth, professor of anthropology. In addition to organizing the testing clinics, Brinkworth is researching the roles of social stress and life experiences on immune function and COVID-19 transmission and severity among Rantoul workers.

“We also want them to tell us what misinformation they may have received and what their needs are—all of that affects where we go and what we try to do next,” she said. “The circumstances here in Rantoul reiterate what’s happening all across the Midwest and globally.”

Added Korinta Maldonado, professor of anthropology and American Indian studies: “These groups deserve not only equal access to testing and health care but also to knowledge about virus transmission. By producing the research knowledge collaboratively and reporting the findings back to these communities, we can find better, smarter mitigation strategies.”

Whitaker called research project “incredibly complex,” adding that while U of I’s initial response to the Rantoul cases was only to help curb the pandemic, the accompanying research has come together in “kind of an amazing and beautiful way.”

“We're still working to define that and integrate the pieces,” Whitaker said. “Microbiology and ethnography are not usually in the same room.”

Editor's note: For more stories about how experts, students, and alumni are learning and looking ahead during this challenging time, visit the Moving forward from COVID-19 page.